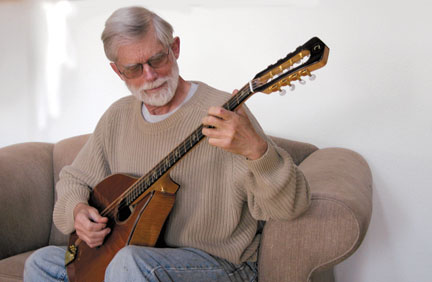

Late-Blooming Luthier

Herb Taylor ’62 has carved a career out of retirement—and unusual woods.

Blending a lifelong love of all things artistic and musical with the time found in retirement, Herb Taylor ’62 has fashioned a late-blooming career as a luthier. Taylor was six years into retirement when he made his first stringed musical instrument—a mountain dulcimer for himself. A friend was so impressed he placed an order for an octave mandolin.

Ten years later, Taylor is still creating beautiful, one-of-a kind, stringed instruments of his own design. “Primarily, I make Irish bouzoukis—the mainstay of my business—citterns, and mandolins,” says Taylor. “Most of my customers come from showings at arts festivals and by word of mouth.”

To accommodate the needs of his craft, the Kentucky native has transformed the cellar of his Golden, Colo., home, nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, into a multiroom workshop. He does the bulk of his work at a well-lit workbench in one room, using chisels and planes and other small tools; a second room holds a drum sander, band saw, and other heavy tools; and a third is a drying room for his supply of wood. One last space is reserved exclusively for spraying on a water-based lacquer finish—the final stage in the creation of an instrument.

Art and music have always had a place in Taylor’s life, beginning with the trumpet in grade school. By college he was playing the French horn in the Swarthmore orchestra—he donated his old French horn to the College’s Music Department in 2009—and sculpting art from wood. He has also done bas-relief woodcarvings and was a painter for many years. “I recently ran into Lisa Menn ’62 at a concert in Boulder,” says Taylor. “She still has a sculpture I made while I was at Swarthmore.”

Taylor played the French horn in the Brico Orchestra in Denver for many years, but, in 1990, the removal of a brain tumor resulted in loss of the hearing in his right ear. “That put an end to orchestra playing,” he says, “because I couldn’t hear the players to the right of me.” With this significant life change, he turned to folk music—thus the desire for a mountain dulcimer—also playing the banjo, autoharp, and harmonica during that period. Currently, he plays in the Denver Mandolin Orchestra.

A self-taught luthier, Taylor admits to having developed his own way of making the instruments, preferring woods that no one else uses, such as goncalo alves, cherry, redwood, and curly makore. He avoids plastic bindings and heavy sunburst stains. “I almost always seem to prefer the “road less traveled,” he says.

Asked to describe the process of instrument making, Taylor replies, “There are about 400 steps!” He agrees to an overview: After drafting a plan, Taylor always makes the parts of the instrument in the same order—neck, sides, and then top and back of the body. The neck comes first because it’s tedious, he says, and needs to be completed so he can fit it into a mortised neck block to connect it to the body’s rim. Once the sides are bent and the rim is made, he glues on the top and back. Next, the more creative work—Taylor applies strips of wood and marquetry to decorate the edges. Nearing the end, he sands the wood smooth, sprays on a finish, and allows the instrument to cure for several weeks before wet sanding and buffing the finish. Lastly, all the pieces of metal such as strings, tuning machines, and tailpiece are attached.

With an M.F.A. in printmaking from Yale and later a master’s in computer science from Denver University, Taylor has dabbled in careers—an art teacher in Vermont and Colorado, a letter carrier, and a software engineer—the job from which he retired in 1994. Since 1973, however, he has been most devoted to mountain hiking and climbing, with a special affinity for the canyon country of the Colorado plateau and the canyons of southern Utah. Today, he prefers backpacking trips or easier climbs, still spending a month in the canyons of southern Utah each spring and fall. Often, he is leading other hikers. “I expect,” he says, “there are only a couple dozen people in the country who know the canyon country like I do.”

Reflecting on the uniqueness of each of his wood creations, Taylor says: “You have to do all the work before you know if the instrument is good. Each experience is based on the experiences of making all the rest. Besides, I’m like an artist; I don’t want to paint the same picture twice.”

Email This Page

Email This Page