Analyze and Evaluate

Time-tested tendencies surface among alumni living in Cairo

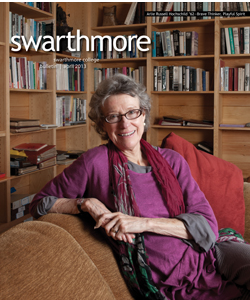

Last summer, Charlie Huntington ’12 assisted with Swarthmore’s Middlebury-Monterey Language Workshop. This summer, he’ll be finishing his stint in Cairo. Photo by Laurence Kesterson

It was only as the plane made a sweeping turn over Cairo proper, and I glimpsed the Nile River, a surprisingly slender blue vein almost lost in the sprawl, that I had my Dorothy moment: I most certainly was not in Swarthmore anymore. I’d spent four years hardly ever leaving Swat, even filling the summer months with on-campus jobs, RA training, and cross-country preseason training. I couldn’t seem to leave the place, and I certainly didn’t want to.

For four years, I was happy to ensconce myself in that safe space, grappling with Arabic, writing essays in McCabe, and racing through class readings during my breakfast in Sharples Dining Hall. Last spring, when I accepted a yearlong internship in the office of communications at the American University in Cairo (AUC), I felt relief that my postgraduation plans were set, for I had more urgent matters to attend to—prepping for Honors exams and signing up for Senior Week events.

The reality of my situation sank in quickly, however, in August as I traveled to my apartment on Zamalek, an island in the Nile. I asked the driver where we were in my best Fusha, the literary dialect of Arabic used throughout the Middle East. He frowned and answered me in broken English. At least he understood the question! The Arabic I’d learned at Swarthmore was akin to Shakespearean English and hopelessly ill-suited for practical conversation, unlike my cabbie’s Cairene Arabic—the equivalent of modern American slang. I majored in linguistics, so the struggles ahead promised to be as fascinating as they would be frustrating.

Thanks to the close-knit worldwide Swarthmore community, I had help adjusting to this new dialect and culture. A few alums work and study at AUC, Egypt’s only liberal-arts-oriented university. As diverse as our journeys are from Swarthmore, Pa., to Cairo, Egypt, we’re all still scholars at heart, invested in our studies, and fascinated by the social upheaval around us.

One of my new colleagues is Ann Lesch ’66, associate provost for international programs at AUC. She was introduced to Cairo in 1968, during the first intensive summer session at AUC’s Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA). “That was a very different time, of course,” she recalls. “Cairenes were still in shock from the defeat of the June War, and with all the censorship going on, everybody was afraid to talk politics.”

In contrast, since the ouster of President Hosni Mubarak in 2011, you can’t find an Egyptian without a political opinion to share. Raise the subject of current president Muhammad Morsi, and you’ve begun a conversation that will last the length of any crosstown cab ride. But talking politics here in Cairo is more than a great way to practice one’s Arabic—it satisfies the time-tested Swattie desire to analyze and evaluate all we encounter. We find ourselves debating possibilities for social change that would be dismissed as outlandish in the United States.

political opinion to share. Raise the subject of current president Muhammad Morsi, and you’ve begun a conversation that will last the length of any crosstown cab ride. But talking politics here in Cairo is more than a great way to practice one’s Arabic—it satisfies the time-tested Swattie desire to analyze and evaluate all we encounter. We find ourselves debating possibilities for social change that would be dismissed as outlandish in the United States.

“The questions Egyptians are asking and the conversations they’re having don’t happen back home,” notes another of my AUC colleagues, Sara Sayess ’76, associate provost for academic administration. “So much of what we debate here is no longer at stake in the U.S.”

Here in Cairo, the vocal demands for Morsi’s resignation, and the many rocks and Molotov cocktails thrown in support of democracy, coexist with an innate distrust of all elected leaders. The actions Egyptians take, legal and otherwise, are compelling to witness.

Lissie Jaquette ’07, a fellow in the same CASA program that Ann attended 45 years ago, joins me in observing the dramatic shifts in Egypt. “Even at the darkest moments during the transition, I find reason for optimism in the multitude of small independent initiatives that have been started in the past couple years,” Lissie says. “What is at stake in the transition we’re seeing now isn’t just political freedoms or the economic condition,” she adds. “It’s people joining together to create new initiatives, new spaces for expression—whether that’s directly political or not.”

Lissie’s words are echoed in some comments by Ann, who, as president of Swarthmore’s student council, circulated a petition protesting the Vietnam War in spring 1965. Ann also organized a popular weekly lecture series in sociology and anthropology, fields not established at Swarthmore in the ’60s. Now Lissie, a Columbia University graduate student in anthropology who majored in sociology and anthropology at Swarthmore, examines life in Cairo through those lenses. “Sociology and anthropology theory, particularly from Professor Farha Ghannam’s courses, continues to structure and enrich the way I see and understand the world,” Lissie says.

While Ann and Lissie’s fascination with the city is more political and sociological, mine is chiefly language based. I share that orientation with the other Cairo alumni. “Arabic has an incredible order and efficiency to it, and the Egyptian colloquial strips it down to the essence of communication, while also adding things full of emotion and imagery,” Sara observes. She and I marvel at the ritual greetings that friends exchange: a handshake, an air kiss on each cheek, and the recitation, as fast as possible, of a slew of greetings: “Good evening! How are you? What news? What are you doing?”

Lissie, a much more experienced student of Cairo than I, sees complete cultural and linguistic fluency as near impossibilities. “I’ve recently become fond of the idea of being ‘asymptotically fluent’ when it comes to Arabic,” she says. “Cultural knowledge is the foundation of fluency—you can understand every word someone is saying but still be completely lost if you don’t recognize an oft-repeated line from a famous movie, the advertising jingle from an ’80s commercial, or references to the Quran. Having that background is true fluency.”

Even if mastery of the cultural and linguistic differences seems elusive, we keep trying. Riding the bus each day, I read a novel in Arabic, occasionally consulting my dictionary. Sometimes I sit next to Ann, a former political science professor who annotates the days’ news stories. Or maybe my neighbor is George Scanlon ’50, AUC professor emeritus of Islamic art and architecture, who comes to campus most days, because, as he says, “that’s where the library is.”

I also think of my father, Frank Huntington ’74, whose hobby is preparing courses in constitutional law and American history as he anticipates the day he stops practicing law and starts teaching it. I’m no longer at Swarthmore, but like-minded, lifelong learners are all around me. In a strange land, I find that reassuring.

Charlie Huntington ’12 will complete his internship in Cairo in June, then intends to continue working in academic settings or teach high-school English. He hopes to eventually pursue graduate studies in comparative literature.

Email This Page

Email This Page