Unlikely Scientists

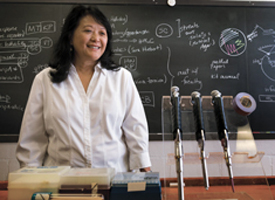

Microbiologist Amy Cheng Vollmer unites two cultures in her ‘only-at-Swarthmore’ lab experiment

Economist Philip Jefferson added some new tricks to his bag of teaching techniques after “apprenticing” in the lab of microbiologist Amy Vollmer, an evangelist for uniting the “two cultures.” Photos by Laurence Kesterson

A music professor playing the pipettes … A historian running the centrifuge … A dean counting bacteria on a petri dish … You never quite know whom you might run into in Amy Cheng Vollmer’s microbiology lab—and she likes it that way.

Every summer, Vollmer, professor of biology, invites Swarthmore faculty members and administrators to spend a few days working in her lab. Philip Jefferson, Centennial Professor of Economics, and Cheryl Grood, associate professor of mathematics, volunteered to be the first guinea pigs, in 2005. They were followed in 2007 by Barbara Milewski, associate professor of music, and Bruce Maxwell ’80, formerly of the engineering department. In 2011, Professor of History Tim Burke donned the lab coat. And in 2012, Leslie Hempling and Melissa Mandos of the dean’s office proved that administrators can cultivate bacteria, too.

The main purpose behind Vollmer’s embedded-faculty program is to break down the wall that divides the sciences from the arts and humanities—the “two cultures” made famous (or infamous) by C.P. Snow in a lecture in 1959.

“I read Snow’s lecture, and my reaction was that it’s the same today, if not worse, even at a liberal arts institution like Swarthmore,” Vollmer says. She mentions an eye-opening study, conducted by Professor of Engineering Lynne Molter ’79 in the early 2000s that showed how Swarthmore students fulfill their distribution requirements. A third of the humanities and social-science majors took only three natural science courses (the minimum requirement for graduation) and did not take a single course with a lab component. These students missed the chance to see for themselves the main way that scientists acquire information about the world.

Vollmer thinks that lab work is particularly important for students because the process of doing science is largely hidden both in the media and in scientists’ own writing. “It is like the bottom of the iceberg, which you don’t see but which makes up 90 percent of the iceberg,” Vollmer says.

Swarthmore has now changed its graduation requirement so that students must take one natural-science course that includes a lab component. But the new rule, Vollmer says, addresses only one part of the problem. “When I looked at those data, I said to myself that the students pick the courses, but their advisers have to approve them. The advisers, too, may have science phobia or at minimum are uninformed about what matters in the process of science.”

That was why Vollmer offered other professors the chance to work in her laboratory. Grood was the first to jump at the opportunity. Jefferson came along a little later. “One day as I was walking through the coffee bar, he stopped me and asked if he could watch a controlled experiment being conducted,” Vollmer says. “I told him the good news and the bad news: You can come to my lab, but I don’t allow people to just spectate.”

Jefferson showed up at her lab the next morning. But he still didn’t want to put on a lab coat. “I told Philip, I’ll just drape the lab coat over the chair here, because it gets cold. Within a week he was wearing it, and at the end of the summer he gave a talk to his department wearing the coat!” Vollmer says.

Jefferson has since become one of the most enthusiastic evangelists for the program. In 2005 he wrote an article about his experience for The Chronicle of Higher Education. His main motivation had been to understand better how scientists design experiments, because there has been a movement in economics toward mimicking the approach of natural scientists. He was very impressed with the “discipline” he learned in Vollmer’s lab, the design of step-by-step protocols to eliminate possible sources of error, and it inspired him to design statistical protocols for use in his econometrics course.

With her embedded-faculty program, Amy Cheng Vollmer aims to break down the wall between the sciences and humanities.

Jefferson also learned something he hadn’t expected. Vollmer would sometimes stop him and Grood from starting on a task they couldn’t finish that day. “You talk about a long-term impact, not only on my teaching but my own research,” he says. “I learned that you can’t ask for too much from the day. Now, when I teach students, I will say, ‘This is a good stopping point.’ Your work has a rhythm, and you need a stopping point. It’s like a rest in music.”

Burke, on the other hand, was fascinated to see how Vollmer dealt with people with a broad range of competence in the same laboratory, from her “fumble-fingered” history colleague to a first-year student to a highly skilled rising senior.

“Yes, I learned from the students,” Burke says. “I think they found it very amusing.” But at the same time, it was instructive for them, he adds. “It was a very heartening demonstration of Amy practicing what she preaches. She is always pushing this notion that scientists have to be willing to engage the public across a wide range of science literacy. She was modeling for the students what that’s like.”

Jefferson and Burke, who are on the steering committee for Swarthmore’s new Institute for the Liberal Arts, see Vollmer’s initiative as exactly the kind of interdisciplinary contact the institute should promote. And in fact, the institute has already sponsored another initiative of Vollmer’s that began in fall 2012.

“I stuck my neck out last spring and wrote to the president and provost to propose a science café for the staff,” Vollmer says. “They replied almost immediately. Rebecca [Chopp] said this would be a perfect thing for our Institute for the Liberal Arts to sponsor as an inaugural event.” The Second Tuesday Science Café gives the staff and faculty a chance to eat lunch, hear a faculty member discuss his or her work or other scientific matters of current interest, and ask questions.

So far the cafés have been a hit, drawing more than 80 people each time and straining the capacity of the Scheuer Room in Kohlberg Hall. In September, Vollmer lectured about bacteria and antibiotics and the never-ending battle between microbes and our immune system. The next three lectures in the series were given by Lynne Steuerle Schofield ’99 (statistics), Michael Brown (physics), and Nick Kaplinsky (biology). “Most of the time our work happens behind closed doors, and our interactions with staff members tend to be limited,” says Kaplinsky. “This is a great chance for faculty to do what we do best—teach—for an audience who otherwise would not find their way into our courses.”

Why does Vollmer devote so much energy to this kind of outreach, which is not normally rewarded in academia? In part it’s because she thinks all scientists should do it. Also, it comes naturally to her. “I think I’m one of those people who just naturally looks for connections,” she says. “Maybe it came from growing up as a Chinese American, when there was nobody else Chinese at my school, until my sister enrolled. I’m constantly looking for what people have in common.”

And Swarthmore, too, plays a role. “I think the environment here encourages intellectual risk taking,” she says. “I often tell my friends about what I’ve been doing, and they shake their heads and say, ‘Only at Swarthmore, Amy.’ Swarthmore has given me the freedom to be me.”

Listen to Professor Vollmer’s Science Café lecture on the immune system here.

Email This Page

Email This Page