What is Africa to Me?

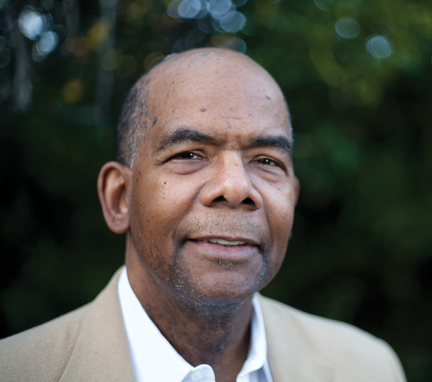

Forty years after serving in the Peace Corps in Gambia, Clinton Etheridge took his family on a pilgrimage to Africa.

What is Africa to me;

Copper sun or scarlet sea,

Jungle star or jungle track,

Strong bronzed men, or regal black

Women from whose loins I sprang

When the birds of Eden sang?

One three centuries removed

From the scenes his fathers loved,

Spicy grove, cinnamon tree,

What is Africa to me?

—from “Heritage” by Countee Cullen (1903–1946), Harlem Renaissance poet

IN SUMMER 1971, MY GIRLFRIEND DEIDRIA MARTIN VISITED ME IN GAMBIA, WEST AFRICA, where I was teaching math as a Peace Corps volunteer. Because of our relatively light brown skin, Gambians thought Deidria and I looked like members of the Fulani tribe and affectionately gave us Fulani names. I was Lamin Jallow and she was Cumba Jallow.

After Deidria and I married in 1974 and started a family, we often talked about going back to Gambia with our children—but Deidria ran out of time. She died of a stroke in August 2008 at age 59.

About a year later, I proposed to my three adult children—Neil, Clinton III (or “CAE”), and Lauren—that we travel to Africa as a family in summer 2011, taking my 4-year-old granddaughter Brianna with us. Ostensibly, the trip would fulfill the dream Deidria and I had for our family of returning to explore our roots and links to Africa as black Americans. But at a deeper emotional level, the real purpose would be to strengthen our family bonds now that our wife, mother, and grandmother had passed away.

In Gambia, I could show my family Latrikunda School, where I taught from 1970 to 1972. I could show them the African compound in Mintehkunda in Bakau, where I lived as a Peace Corps volunteer and where Deidria stayed when she visited in 1971. And like many black Americans before us, we could visit two sacred shrines of slavery: Goree Island in the harbor of neighboring Dakar, Senegal, and Juffureh Village in Gambia, to which Roots author Alex Haley had traced his African ancestor, Kunta Kinteh.

I was overjoyed and excited about going back to Africa after 40 years. I trusted that Gambians would be the same warm, friendly, hospitable people I knew decades earlier—even though development in the ensuing years would have produced a busier, more populous country. I expected that my adult children would experience a heady mixture of culture shock and wonderment. But it was harder to know what Brianna would be thinking and feeling. After all, she was only 4 years old. I first went to Africa at 23; compared to me, my granddaughter was a tabula rasa on which her African experience could be written with virtually no preconceived notions.

We made that trip last July, and it was very much a pilgrimage—in the sense of a journey of great moral or spiritual significance.

When Grandaddy Comes

When my daughter Lauren first told Brianna about going to Africa, she showed my granddaughter an Internet picture of the Sheraton Gambia beachfront hotel at which we would be staying. All my immediate family members—both sons, daughter, and granddaughter—now live in landlocked Huntsville, Ala., about halfway between Nashville and Birmingham. Brianna had only seen a beach on TV or in a book—never in person. Lauren helped conceptualize the trip for her by saying, “When Granddaddy comes, he is going to take us to the beach.”

For days afterwards, Brianna put on her little bathing suit and wandered around the house asking yearningly, “When is Granddaddy coming to take us to the beach?” Lauren told me she even found Brianna sleeping in her bathing suit one night.

Of course, we won’t really know what Brianna thought of the family pilgrimage to Africa until she is much older. (We took plenty of pictures to refresh her memory.) But I observed a child who was seeing and experiencing so many new and interesting people, places, and things—like the bemused Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, who tells her dog: “We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto.”

I believe children have some innate democratic capacity to engage with other children—and, with a child’s heart, Brianna tried to hug every baby and play with every child she encountered in Africa. Unfortunately, it seems this capacity erodes as children mature and learn to be influenced by things like race, religion, language, dress, and country of origin. I wonder whether Brianna will mature differently because she visited Africa at age four?

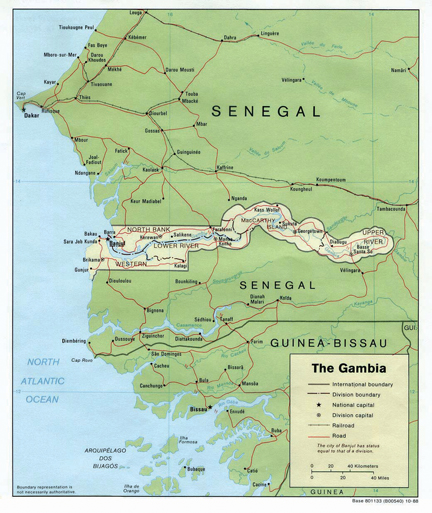

The unusual geography of Gambia—it is bordered only by Senegal—stems from the colonial era, when the British occupied the river valley and the French colonized the surrounding countryside. Language differences persist among educated Gambians and Senegalese, whose common language is Wolof.

Lessons Learned

Returning to Africa made me realize that I learned several important lessons there as a young man—commonsense universal truths that an intense personal experience first taught me.

Lesson one: People are more alike than they are different.

When I scratched the surface and got to know Gambians and Senegalese as friends, I found the Africans had the same dreams and hopes and fears for themselves and their children as Americans. I shared this common humanity with my African friends, even though I was born and raised in one of the world’s richest countries—a land of relative opportunity that offered many more “life chances.” By contrast, my African friends were born and raised in countries of extreme poverty and limited opportunity. Yet last July, I saw the pride with which my Gambian and Senegalese friends spoke about their sons and daughters, who were bettering themselves by studying or working in the United States, England, France, Sweden, or Denmark.

I was reminded of Shylock in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. In Act III, Scene 1, the Jewish moneylender declares: “Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs … senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means … as a Christian is?

“If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?”

Lesson two: Respect for Islam

By living in predominantly Muslim Gambia for two years, I learned that Islam is one of the world’s great religions. Besides seeing devout Muslim friends pray five times a day, I twice experienced Ramadan—the high holy month of fasting, during which Muslims refrain from eating, drinking, and smoking during daylight hours in order to practice patience, spirituality, humility, and submission to Allah.

Christianity is a positive force in the world and in the lives of most Christians. Islam is also a positive force in the world and in the lives of most Muslims. After 9/11, I was surprised and disappointed to see Islam portrayed as a “terrorist religion” in some quarters of the United States. Because of Peace Corps Gambia, I knew better.

Dié Sylla, the wife of Sambou Toure, sewed African garments for Etheridge family members. Clinton received an elegant netti abdou—a three-piece outfit. “People say I look regal in the garment Dié Sylla tailored for me,” Etheridge says, “almost like an African prince.”

Lesson three: I am a tubaab—but a beloved African-American tubaab like Alex Haley.

In the 1960s, many young African-Americans were “black and proud”—and fascinated with Africa. We sought to identify with Africa by wearing our hair in afros and dressing in dashikis. It was a heady, intoxicating time. This was the world view that led me to Peace Corps Gambia in 1970; I was grappling with the burning question posed by Countee Cullen: “What is Africa to me?”

As a black Peace Corps volunteer 40 years ago, I fell in love with Africa. But I didn’t know quite how American I was until I went there. With anguished disappointment, I learned that too much time and space had separated me and my African-American ancestors from Africa. Although my heart and spirit wanted to be African, my American upbringing said otherwise. When I walked around the Gambian capital Banjul with my Peace Corps friends, children in the streets would say to us: “Tubaab, tubaab, may ma buréy.” Tubaab, tubaab, give me a penny.

In the Wolof language of Gambia and Senegal, the word tubaab is frequently translated as “white man.” But it is better defined as “non-African,” which is what the white European colonialists were—the British in Gambia and the French in Senegal.

In Gambia, I happened to meet Alex Haley in 1972, while he was researching Roots, the book and TV-miniseries that later took America by storm. In many respects, Alex Haley put Gambia on the map and made Juffureh Village a worldwide tourist attraction. Yet Alex Haley and I are both African-American tubaabs. But we’re also both beloved by the Gambians—he in a big way and I in a smaller one—because we came to Gambia, “three centuries removed” in the words of Countee Cullen, to give back and to serve.

Lesson four: Judge people as individuals rather than as members of the group you believe they represent.

Lesson four: Judge people as individuals rather than as members of the group you believe they represent.

I taught math at Latrikunda School five days a week for the nine-month school year. Although I believe I was a conscientious and effective teacher, I had a lot of time to read and to think about my life—and about the United States and Africa. In general, the Peace Corps tends to be a reflective, introspective time for volunteers.

One of the books I read during my Peace Corps days was about the founding of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People)—I cannot remember the title of the book after 40 years. I learned the NAACP was founded in 1909 as an anti-lynching organization. I remember reading a gruesome litany of lynchings one Sunday evening, with graphic descriptions of the hideous nature of these crimes—including burning at the stake, dismemberment, and castration. One particularly egregious lynching in 1892 stands out in my memory: Three black men (Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart) were lynched in Memphis, Tenn., because they opened People’s Grocery, a store that competed too effectively with the white-owned grocery across the street. One night, a group of armed white men attacked People’s Grocery. Moss, McDowell, and Stewart—who defended their property and shot some of the white attackers—were arrested by the authorities. A lynch mob broke into the Memphis jail, dragged them away from town, and brutally killed them. None of the white lynchers was ever brought to justice.

Etheridge’s granddaughter Brianna Erskine made friends easily with Gambian children—exhibiting “an innate democratic capacity.

I got sick to my stomach that Sunday evening, unable to read any more from that book. My blood was boiling about the lynching of those black people. I had a hard time sleeping that night.

The next day, a Monday, I was subdued as I taught math to the schoolboys at Latrikunda. After school, I took a taxi into Banjul and went by the Peace Corps office to check for mail. In those days, everybody else in Peace Corps Gambia was white. I probably shouldn’t have gone to the office that day, for my blood was still boiling.

Then Vince Ferlini, who taught math at a secondary school in Banjul, walked into the office. Vince grew up in an Italian-American family in Hartford, Conn., and had gone to Notre Dame before joining the Peace Corps. We were both members of the Peace Corps Gambia basketball team. During our two years there, Vince became my best friend in the Peace Corps.

But at the office in Banjul that afternoon, I tried to avoid speaking to Vince, until he plaintively looked me in the eye. I realized then that Vince knew nothing about the lynchings of Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart. Vince had no connection to the gruesome litany of lynchings I had read the night before. He was just my friend and fellow Peace Corps volunteer.

After leaving Gambia, I didn’t see Vince for nearly 40 years—until we met at the Gambia Mission to the United Nations in New York—where my family obtained our visas the day before we flew to Africa. Vince and I arranged our reunion through emails and phone calls. When we first saw each other, we smiled and hugged affectionately; we were like two long-lost brothers.

Lesson five: Stereotypes about Africa die hard.

My Peace Corps training provided me with a very good cultural introduction to Africa. Wolof instructors taught us the basics of the language. We saw pictures of Gambia and Senegal and heard tapes and records of traditional African music played on the kora—a stringed instrument sometimes called an “African guitar.”

Moreover, the previous summer (1969), I had worked with a Gambian college student and a French-speaking Senegalese student. But there is no substitute for experience. When I landed at the airport in Dakar, Senegal, in August 1970, I was surprised that the porters were speaking French—a mark of sophistication in the United States. I was also surprised to find tall buildings in Africa, albeit just 10 stories. I was forced to confront my own stereotypes about Africa and to wonder why those stereotypes die hard.

Malcolm X provided his viewpoint on this question in a 1965 Detroit speech: “Having complete control over Africa, the colonial powers of Europe had projected the image of Africa negatively … jungle savages, cannibals, nothing civilized.” This is the “Dark Continent” image of Africa that has been programmed into the Western psyche, for example, by Tarzan movies and novels like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Through Peace Corps Gambia, however, I learned that the “darkest” thing about Africa is our ignorance of it. To be sure, Africa suffers from poverty, famine, disease, war, and genocide—stark realities that are part of Africa today. But these are not the whole story. There is a more complex reality to Africa that is frequently obscured or eclipsed by the stereotypes and the clichés. For example, many Americans would be surprised to learn that Ghana, in West Africa, has enjoyed one of the world’s highest economic growth rates over the last few years: 8.4 percent in 2008, 4.7 percent in 2009, and 5.7 percent in 2010—according to the CIA’s World Factbook.

Malcolm X provided his viewpoint on this question in a 1965 Detroit speech: “Having complete control over Africa, the colonial powers of Europe had projected the image of Africa negatively … jungle savages, cannibals, nothing civilized.” This is the “Dark Continent” image of Africa that has been programmed into the Western psyche, for example, by Tarzan movies and novels like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Through Peace Corps Gambia, however, I learned that the “darkest” thing about Africa is our ignorance of it. To be sure, Africa suffers from poverty, famine, disease, war, and genocide—stark realities that are part of Africa today. But these are not the whole story. There is a more complex reality to Africa that is frequently obscured or eclipsed by the stereotypes and the clichés. For example, many Americans would be surprised to learn that Ghana, in West Africa, has enjoyed one of the world’s highest economic growth rates over the last few years: 8.4 percent in 2008, 4.7 percent in 2009, and 5.7 percent in 2010—according to the CIA’s World Factbook.

Since there is no substitute for experience, and because stereotypes about Africa die hard, I believe every black American should go to Africa at least once—if only for a little while. Only by doing so can a black American get a reality check on the burning question posed by Countee Cullen: “What is Africa to me?”

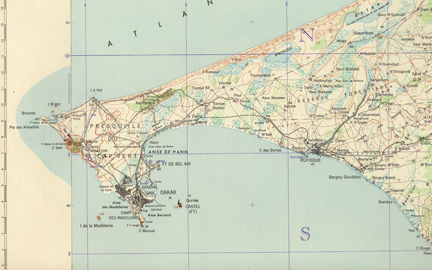

The Etheridge family’s pilgrimage to Africa included a visit to Gorrée Island off Dakar, Senegal, where enslaved Africans were put aboard ships for the Middle Passage to the Americas.

My Gambian friend Hayib Sosseh

Hayib Sosseh and I met as fellow teachers at Latrikunda School, where we formed a ready bond that has lasted a lifetime. He is a thoughtful, elegant gentleman and a gifted teacher, perhaps because he descended from the griot class within the Wolof tribe—the storytellers and the keepers of the oral tradition.

Hayib welcomed me into his African world—as did his Gambian friends and relatives. I spent long hours and weekends at Hayib’s compound in the Half Die section of Banjul—sleeping overnight, eating communally, drinking ataya (an African tea that men drink as they sit around the compound and talk), and generally imbibing Gambian culture.

Peace Corps Gambia encouraged volunteers to “live at the level of the people” and avoid the expatriate enclaves for which the British colonialists were noted. But because of Hayib, I was able to experience Gambian society at a deeper, richer level than most of my fellow Peace Corps volunteers.

I was in Gambia less than six months when Hayib took me to neighboring Dakar, Senegal, for Christmas 1970 to visit his Senegalese cousins, the brothers Sambou Toure and Ndary Toure.

Hayib and his cousins, like many Senegalese and Gambians, speak Wolof, a major language of the region, and have friends and relatives on both sides of the border.

But because of colonial history, educated Senegalese tend to speak French and educated Gambians tend to speak English.

In 1970, Sambou was a premed student at the University of Dakar and his brother Ndary was a high-school student at a lycée in Dakar.

Etheridge (left) made friends with Hayib Sosseh, a fellow teacher at the Latrikunda School, who invited the Peace Corps volunteer to spend time at his family compound. There, he met Hayib’s cousin, Ousman Njie (right). “They welcomed me into their African world,” Etheridge says. He taught math for two years at the school, where he was photographed (opposite) in 1971.

Some 40 years later, my family and I met the Toure brothers in Dakar. Sambou is now a Senegalese politician—the president of the regional assembly in Kaolack, one of Senegal’s larger cities. As a regional politician in a predominantly Muslim country, Sambou Toure now wears khaftans and marakiis—pointy Moroccan-style slipper shoes. Ndary Toure serves as deputy chief justice of the Senegalese Cour Supreme (Supreme Court) and wears Western-style clothes, like most cosmopolitan Senegalese.

In Dakar, both brothers showered my family with African hospitality.

Sambou hosted us for dinner at his compound in Dakar with a sumptuous feast of Senegalese benachin, domodaa, and chicken yaasa prepared by Sambou’s wife, Dié Sylla. Neither my French nor my Wolof is any good, but thankfully Sambou and Ndary now speak English well enough to communicate with the African-American tubaabs in the Etheridge family.

We visited Ndary at the Cour Supreme, where I reminded him how we first met in 1970 when he was a student at the lycée. Using an American colloquialism, I then told Ndary: “I knew you when you were knee-high to a grasshopper, and now your name is up there in lights.” He laughed when I told him he had become a “big boss, a patron.”

A Tribute to “Teacha”

My three adult children have known me all their lives. I was in the delivery room to witness each of them come into the world. Over the years, as a father, I tried to love and nurture each as best I could.

But when Deidria, my wife of 34 years, died tragically of a stroke at age 59 in 2008, I was thrown into a life crisis. Suddenly, I became a widower living alone in the Oakland house in which our children grew up and from which they left the nest. I realized I needed my children and their love as much as they needed me. I solemnly told myself, “I’m the only parent they have now!” I was determined to spend as much quality time with them as possible.

Etheridge’s three children—Neil, Lauren, and Clinton III—commissioned a painting of Etheridge based on one of two extant photos showing him teaching math to Gambian boys as a Peace Corps volunteer.

Some 40 years ago, someone took a photo of me teaching the Gambian schoolboys at Latrikunda. Several months before our family pilgrimage to Africa, my daughter Lauren was looking at a copy of the picture and called me “Teacha.” (“Teacha” or “Teacher” was the respectful form of address with which the Gambian schoolboys spoke to their teachers back then.) On the last day of our trip, as I was bedding down in the hotel in Dakar before our 8 a.m. flight to New York, my three children knocked on my door. To my surprise, they entered and presented me with a large oil painting of that classic classroom picture.

Lauren told me the “Teacha” painting—which they commissioned from a Dakar street artist—was a token of their appreciation for me and the pilgrimage. In two weeks in Africa, she said they learned how the formative experience of Peace Corps Gambia—about which they had heard for much of their lives—had helped shape me into the man they knew.

This tribute to “Teacha” was one the greatest experiences of my life. I knew then our family pilgrimage had been a success; my children had bonded more deeply with their single-parent father, and my children had come to appreciate my links and ties to Africa—and their own too. My children had grappled with and found their own tentative and preliminary answers to the burning question “What is Africa to me?” After they left, I stared at the painting in silence, basking in Etheridge family love. I cried.

“Clinton, doo fi ñówati waay?”

In addition to 200,000 ordinary visitors a year from around the world, dignitaries such as Pope John Paul II, Nelson Mandela, President Bill Clinton, and President George W. Bush have visited Gorrée Island in Dakar and its infamous Slave House.

At the center of the Slave House is the “Door of No Return,” a coffin-sized portal that looks onto the Atlantic Ocean at the closest point on the African continent to the Americas. According to legend, the “Door of No Return” was the last foothold captured Africans had on the Motherland before embarking on the Middle Passage. Like Kunta Kinteh of Roots, my chained African ancestors symbolically passed through their own “Door of No Return” into slavery on an American plantation.

As I was leaving Gambia in summer 1972, after two years there in the Peace Corps, many Gambian friends were saying in Wolof, “Clinton, doo fi ñówati waay?” “Clinton, you won’t be coming back here anymore, will you?”

But last July, standing in the “Door of No Return” at the Slave House in Dakar harbor (with family nearby, overcome with emotion and close to tears) I gave a resounding “yes” to “Clinton, doo fi ñówati waay?” Yes, I have come back! I have come back!

Email This Page

Email This Page