To the Ends of the Earth—to Save a Language

Linguist K. David Harrison goes out on a limb to save the planet's endangered languages and probably knows the word for "limb" in many of them

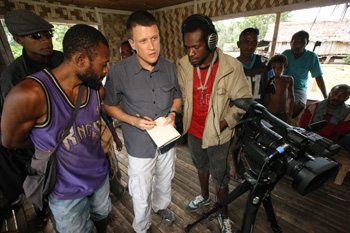

Linguist K. David Harrison (center) works with John Agid (left) of Matugar villiage, Papua New Guinea, to document Matukar Panau, an endangered Oceanic language. Only 600 speakers of the language remain in just two small villiages. Matukar Panau is featured in a new talking dictionary created by Harrison and fellow linguist Gregory Anderson. Photo by Chris Rainer, National Geographic

K. David Harrison is not a botanist. But walking through the Chilean rainforest with Teresa Maripan, he listened with fascination as she pointed out the tiniest details of the forest’s flora and explained the important ritual and medicinal uses of some of the specimens. Interesting as the facts about the mosses, leaves, flowers, and plants were, what really excited him was the language in which Maripan was describing them. Huilliche is spoken only in Chile’s Los Lagos and Los Rios regions by fewer than 2,000 people. Most of the Huilliche speakers are older adults, whose children mostly know only Spanish. Consequently, Huilliche is in decline. Harrison’s task—and the reason for his visit to the area—was to help preserve the language from extinction. When he’s not teaching linguistics as an associate professor at the College, rescuing endangered languages is what he does.

CIRCUMVENTING EXTINCTION

If a language becomes extinct, so does the culture it describes. Half of the world’s 7,000 languages, some of which exist only in oral form, are endangered for reasons that include cultural changes, government repression, and the dominance of imperial languages, says Harrison. To counteract these threats to small languages, he and fellow linguist Greg Anderson, co-director with Harrison of The Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, regularly embark on Indiana Jones–style adventures to some of the most remote corners of the globe in search of the few souls who still communicate via these vanishing tongues. In notebooks and filmed interviews, they record the words of native speakers—treasure troves of wisdom, daily life, culture, rituals, and practices. Sometimes they come upon a language hitherto unknown to science, such as Koro, a highly endangered language spoken by only a few hundred inhabitants in northeastern India.

“David and Greg will circle the planet to hear the last whispers of a dying language. They are ‘The Linguists,’ ” reads the caption to a Web promotion of their 2007 movie of the same name—a colorful, exciting, and sometimes humorous documentary tracking their research. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2008, where it was lauded as “the talk of the town” by Reuters.

“The work we do is intellectually thrilling, because we are advancing science and making what are often the first-ever recordings of previously undocumented languages,” Harrison says. “It’s also satisfying because it has a positive social impact on communities that may be struggling to sustain their languages, and their very identity.”

Woman gather and display traditional clothing of the Remo culture in India. Remo is a highly endangered language that can now be found online in a talking dictionary. Photo by Opino Gomango, National Geographic

A particularly rewarding moment came when Harrison was in Siberia, recording epic storyteller Shoydak-ool Khovalyg, a speaker of Tuvan, an indigenous tongue spoken by nomadic peoples of Siberia and Mongolia.

“He could recite large portions of a 10,000-line epic tale from memory,” says Harrison. “He asked me, ‘Who will hear this recording?’ and I told him that anyone around the world who has a computer would be able to hear his story. He replied excitedly, ‘That makes me immortal.’ ”

It is not Harrison’s goal to learn all the languages he saves. “I’m not a linguistic savant, although I do enjoy learning new words and phrases,” he says. “I learn and use whatever I can, and speakers are usually pleased when anyone takes the trouble to learn even a few words of their language. I can carry on a basic conversation in several languages for which there are only a dozen or so speakers,” he says.

Harrison has written two widely acclaimed books chronicling his efforts to revitalize endangered languages and preserve the knowledge inherent in them as well as highlighting the speakers. The Last Speakers: The Quest to Save the World’s Most Endangered Languages, was published in 2010 by National Geographic. Oxford University Press published When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World’s Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge in 2007.

A DIGITAL RESCUE

Since the beginning of this year, digital technology also has been contributing to the preservation of endangered languages. Harrison and Anderson, both National Geographic fellows, have been creating a series of online talking dictionaries, which replay words spoken and recorded by a native speaker, displaying them in transliterated form and spelled out phonetically, accompanied by English translations and photographs. They incorporate the research of Harrison and Anderson and several Swarthmore work-study students as well as the videography and photography of National Geographic Fellow Chris Rainier. National Geographic and the Living Tongues Institute produced the series, and Swarthmore College, the National Science Foundation, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, and National Geographic’s Legacy Fund supported it.

The creation of a talking dictionary begins with the recording of hundreds and eventually thousands of basic words in a language, says Harrison. Student workers and interns spend endless hours processing, analyzing, and organizing the recordings. “Then we put these online, creating a first-ever Internet presence for these languages,” he says.

Jen Johnson ’12 has been working with Harrison for two years on the Siletz Dee-ni Talking Dictionary Project. Siletz Dee-ni is a Native-American language of the Pacific Northwest, the region where Johnson grew up. During summer 2010, at Harrison’s suggestion, she attended a course in Oregon Athabaskan, an Oregon Indian language related to Siletz Dee-ni, and began working in the Endangered Language lab the following fall.

Gaspar Paja and his grandson, Alvin Paja Balbuena, from the Chamacocco community in Paraguay. Gaspar is one of only about 1,200 people who still speak the endangered Chamacoco language. Photo by Chris Rainer, National Geographic

“I work a few hours a week in the lab—it’s my campus job—mostly segmenting audio files, organizing and uploading data to the Talking Dictionary (TD) website,” Johnson says. Last summer, Johnson did fieldwork, funded by a Lang Summer Research Fellowship. In and near Siletz, she took photos and made video-recordings of local flora and fauna and traditional arts and cultural activities to enrich the TD site. She’s increased the dictionary’s entries from about 4,500 to more than 10,000.

“David has been extremely supportive as a boss, teacher, and adviser,” Johnson says. “I admire the energy and passion he puts into language revitalization and what he’s been able to accomplish. He’s tops in so many ways.”

In February, at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Harrison unveiled eight talking dictionaries, which contain more than 32,000 words in eight endangered languages and more than 24,000 audio recordings of native speakers pronouncing words and sentences. One of the positive effects of globalization is that communities whose languages are endangered are beginning to use digital technologies to preserve their languages “to make their voices heard around the world,” says Harrison.

During an AAAS panel discussion on the applications of digital tools to save languages, Alfred “Bud” Lane, one of the last known fluent speakers of Siletz Dee-ni, commented on the project. “The talking dictionary is and will be one of the best resources we have in our struggle to keep Siletz alive,” says Lane. “We’re teaching the language in the Siletz Valley School two full days a week now, and our young people are learning faster than I had ever imagined.”

News of the release of the talking dictionaries roared through the international press like wildfire—drawing tremendous coverage from North America, Europe, and Asia and the Indian subcontinent. As Harrison wrote on The Huffington Post website Feb. 23, “From the rugged Oregon coast to the Himalayan foothills, to seaside jungle villages of Papua New Guinea, small languages are fighting to survive. Pressed by a tide of globalization and a barrage of negative messages telling them their cultures and ways of thinking are outmoded, a global cohort of language warriors are pushing back.”

The talking dictionaries include:

Matukar Panu—an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea, spoken only by the 600 inhabitants of two small villages—had never before been recorded or written

Chamacoco—a language of Paraguay’s northern desert, spoken by about 1,200 people but highly endangered

Remo—a highly endangered and poorly documented language of India

Sora—the language of a tribe in India under pressure to assimilate

Ho—a tribal language of India, with about one million speakers but under pressure from larger tongues

Tuvan—an indigenous tongue spoken by nomadic peoples in Mongolia and Siberia

Siletz Dee-ni—a Native-American language of the Pacific Northwest

An eighth dictionary is dedicated to Celtic languages, and more are in production.

Email This Page

Email This Page