Queer Past Explored

Alumni historians detail personal, institutional journeys

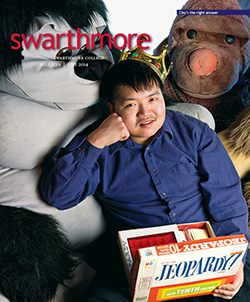

Lauren Stokes ’09 (left), Nayan Shah ’88, and Tim Stewart-Winter ’01 were among the alumni historians who, because of their experience on the margins, have produced queer histories. Photo by Laurence Kesterson

The College’s legacy of largely welcoming and supporting LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) students, faculty, and staff was detailed by three alumni historians and a current student during a sesquicentennial event this April in the Lang Performing Arts Center.

Touching on their personal and professional queer histories were Nayan Shah ’88, professor of American studies and ethnicity and chair of history for the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences; Tim Stewart-Winter ’01, assistant professor of history at Rutgers University–Newark; Lauren Stokes ’09, a Ph.D. candidate in modern European history and co-director of the oral history project Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles: A History of LGBT Life at the University of Chicago; and Ali Roseberry-Polier ’14, a history and gender and sexuality studies major who wrote her thesis on gay and lesbian organizing at Swarthmore in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Pieter Judson ’78, the former Isaac H. Clothier Professor of History and International Relations, moderated the event that was introduced and organized by Farid Azfar, assistant professor of history.

According to Judson, “Swarthmore has a reputation as being queer friendly, but this recent reputation is the product of a lot of very hard work by current and former students, faculty, and staff.” He mentioned in particular his mentor, Eugene Weber, associate professor of German, who became, in 1986, an early victim of the AIDS crisis; and the late Jerry Wood, professor of history.

Two of the panelists noted that Judson’s own history of sexuality course was immensely influential.

“Pieter’s course shaped my life,” Stewart-Winter said. Another mobilizing incident, he said, was “Matthew Shepard’s killing [in 1998]. I organized a vigil under the bell tower.” Another indelible incident occurred a month later, when vandals struck the Intercultural Center, where campus LGBT groups met (and still meet), he recalled.

Stokes also highlighted Judson’s class, saying it was “one of the events that set me on the path to becoming a queer historian.” The other was writing two articles for the Daily Gazette—one about Swarthmore’s queer history, from the 1970s to the late 2000s, the other about the history of graffiti chalkings on campus, some of which were pro-gay and lesbian, while others amounted to hate speech.

Those two articles, said Judson, “are what have become the standard institutional queer history at Swarthmore. They are the canon.”

Shah talked about his student days during the Reagan era, “when asserting our identity was a risk. In the ’80s, we were a small, remote network of people,” despite leaders such as campus horticulturalist Jack Potter, he explained. Potter “was the first person I knew living with AIDS,” said Shah.

A landmark event in Swarthmore’s LGBT history occurred when Richard Sager ’74 established a fund to support conferences and symposia that explore issues of interest to the LGBT community. The first of what was then called the Sager Symposium (later renamed the Queer and Trans Conference) began in 1989 with the topic “Revealing the Unspoken: Gay and Lesbian Studies in Academia.” Shah pointed out the historical significance of the first Sager-funded event, during the College’s 125th anniversary. The topic of this year’s conference, held in February, was “Resisting Violence, Building Queer Safety.”

Though the College has, as Roseberry-Polier noted, “a reputation as being a queer-friendly campus,” she contended, “We can’t pretend that problems don’t exist. There have been ruptures during my time.” She mentioned incidents of vandalism in spring 2013 involving the Intercultural Center. Roseberry-Polier finds parallels between recent “ruptures” and those of 25 years ago, the time period depicted in her senior thesis.

Kenneson Chen ’14, a leader with the current LGBT community, commented during the post-presentation discussion, “I found the panel, from the bottom of my heart, to be brilliant. I had a feeling of belonging, coming face-to-face with LGBT alumni who’d been through this before. It made me feel part of a larger family.”

Reflecting on her experience as a panelist shortly after the event, Stokes said, “It was enormously satisfying, both personally and professionally. We presented a very diverse set of perspectives on what it might mean to look at Swarthmore queerly. I hope that those attending got things out of it that were useful for them and that it sparked conversations and ways of imagining that are perhaps different from the official narrative of the sesquicentennial.”

To read Lauren Stokes ’09’s accounts of the College’s queer history, click here and here.

Watch the queer histories panel here.

Email This Page

Email This Page