Warrior for Equality

Activist and philanthropist James Hormel ’55 dedicates his life to social equality and justice

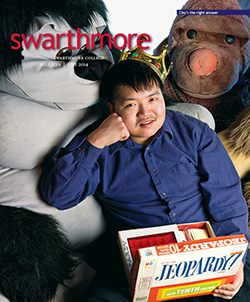

On campus in early May for a Board of Managers meeting, James Hormel takes a breather from meetings. A Board member since 1988, Hormel says that, arriving at Swarthmore in the early 1950s as a transfer student, he’d never known a student body more eager to acquire knowledge and use it. Photos by Laurence Kesterson

As a child growing up in Austin, Minn., in an affluent household in a predominantly white community, James Hormel ’55, the youngest of three grandsons of Hormel Foods founder George A. Hormel, didn’t witness discrimination. So much greater then was his shock when, arriving, age 13, at the Asheville School for Boys in North Carolina, he found “a quiet platoon of male, black caretakers, who served our meals, cleaned our rooms, and looked after the buildings and the lawns,” he writes in his 2011 autobiography Fit To Serve. Even more horrifying was the reaction of bystanders when, on a school jaunt into the nearby town, thirsty and unaware of segregation policy, he used the “colored” water fountain. A crowd of appalled white onlookers gathered. Without understanding the social implications of the incident, Hormel found their reaction bizarre and inconceivable. During that same period, he began to feel attracted to some of his schoolmates, while occasionally dating a girl.

Following high school, Hormel was admitted to Princeton. After a miserable semester there, he enrolled in a tiny, experimental college in Palos Verdes, Calif., and then transferred to Swarthmore, where the students’ social consciousness impressed him. “I know of no student body more eager to acquire knowledge and use it, and no faculty more engaged in offering that experience to students,” says Hormel, today one of the College’s most generous benefactors.

In denial about his sexuality, Hormel fell for pretty, young Alice Parker ’56, whom he married after graduation. They had five children.

“Alice was easy to love,” he says.

Hormel went on to earn a law degree at the University of Chicago, serving for two years as an attorney for a Chicago law firm, then later as dean of students and director of admissions at the university, where he urged Chicago’s administration to admit more women and students of color.

In 1965, at age 32, Hormel and his wife separated. “I was still very much in the closet at the time,” he says. “Even after we separated, it was hard for me to admit to myself that I was a gay man. I had to go back and look at my life and the pretense of how I’d lived it.” During that period, he opened up to his siblings. “My brothers’ acceptance was liberating,” Hormel says.

Wishing to function honestly and openly, he dedicated himself to helping combat prejudice of all kinds.

“I became preoccupied with tearing down racial barriers and eventually eliminating discrimination based on sexual orientation and identity,” he writes in his book. “What came to me after many years of self-exploration and reflection was a mandate to devote my human faculties and financial resources to building a better world—one where equality and personal freedoms were extended to all.”

In 1968, convinced that the federal government was misleading the country, Hormel became active with The New Party and its presidential candidate Dick Gregory, a popular African-American comedian and civil-rights activist. He describes that time as “exhilarating and inspiring but terrible. The 1968 Democratic Convention was a fiasco, and some of my friends in Washington, D.C., suggested I become involved, especially after the Stonewall Riots in 1969, which happened while I was living in New York City.”

Disillusioned with the infighting among the nascent civil-rights groups, Hormel moved to Hawaii to reflect on his experience, then, in 1977, relocated to San Francisco, where he still lives.

Actions of individuals like Anita Bryant and her supporters, whose efforts led to the California initiative to ban lesbians and gays from teaching in the state’s public schools, spurred Hormel to renewed involvement.

James Hormel heads to Kohlberg Hall, where lunch and his fellow Board members await.

“My mission was to defeat that initiative. Against all odds, we did,” Hormel says. Two years later, he co-founded the Human Rights Campaign Fund, and in 1986, provided funding to begin the LGBT Project of the ACLU.

In the early 1980s, the AIDS epidemic erupted, and inspiration no longer sufficed. Hormel recalls, “There was so much fear, so much we didn’t know, that caused people to do outrageous things like quarantine individuals—not just gay people.” He mentions Ryan White, a 13-year-old hemophiliac infected by a tainted needle during a blood transfusion. White’s family was forced to relocate to another state.

Co-founder of several organizations to serve HIV/AIDS victims, Hormel, who lost half his friends to the virus, was instrumental in creating an atmosphere of activism around public health in San Francisco that became a model for the rest of the country.

In 1995, he funded the James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center at the San Francisco Public Library, home to an extensive collection of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender literature, history, and culture. He was appointed to the U.S. delegation to the 1995 United Nations Commission on Human Rights in Geneva, and, in 1996, the U.S. delegation to the U.N. General Assembly in New York City.

Nominated in 1997 to be the U.S. ambassador to Luxembourg, Hormel became embroiled in a harrowing and ugly political struggle to push his nomination through to a vote. Ultimately, President Bill Clinton made a recess appointment, and in June 1999, Alice, Hormel’s children, and his grandchildren were among those who attended his swearing-in.

Hormel was welcomed into the American embassy in Luxembourg as the United States’ first openly gay ambassador, serving for 18 months. With changing attitudes and regulations, other gay appointees have served since or are serving now.

At 81, Hormel is a tall, slender, silver-haired gentleman. With his mellow voice, infectious chuckle, and delightfully cordial nature, he is still every ounce the diplomat.

Hormel met partner Michael Nguyen ’08 at the 2006 Equality Forum awards dinner at the Constitution Center in Philadelphia. He had donated a table to the College for selected LGBT students. Michael was among them.

“Our running joke is that we met when Michael was a sophomore and I was a senior,” Hormel says with a laugh.

He says he understands some people’s reservations about the institution of marriage.

“There are a lot of gay men and lesbians—and nongay couples—who prefer not to be married. Many regard it as an institution of a repressive society,” Hormel says. Nonetheless, he firmly believes that everyone should have the opportunity to marry. “In its current form, marriage has many advantages, and I see no reason why any class of people should be denied these advantages,” he says, recently encouraged by public support for the marriage equality movement. “It indicates a new level of awareness among people generally about discrimination,” he adds.

Says Hormel, “I’ve had plenty of time to visualize a country in which gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people enjoy every single right and freedom afforded to every other American. The question is, ‘When will it happen?’”

Email This Page

Email This Page