A Deal That’s Sweet As Syrup

Dan Werther ’83 has found his niche—as owner of confection company Sorbee International.

After almost three decades of boosting and shaping the enterprises of others—as a lawyer, business operator, and fundraiser—Dan Werther ’83 concluded that what he really wanted was to run his own business. So he bought Sorbee International—a company that began about 30 years ago as a small, sugar-free candy business. The first and largest supplier of sugar-free lollipops to dentists’ and doctors’ offices around the United States, the company produces and sells candy and confection products worldwide.

The Sorbee headquarters sprawl across a large section of the second floor of the Neshaminy Interplex Business Center in northeast Philadelphia. With several small offices bordering a vast central area, the space seems big for a staff comprising only a CEO, CFO, head of marketing and product development, head of sales, and a couple of administrators who handle accounts receivable and accounts payable.

One of the white-walled rooms, “the product room,” is bright with boxes of low-sugar Dream Bars; neatly arranged bottles of sugar-free, lite, and full-sugar syrups; stands bearing sugar-free Crystal Light chewy and hard candy and full-sugar Country Time lemonade candy; and cylindrical containers of multicolored sugar-free lollipops—samples of the 50-or-so products currently being manufactured by Sorbee.

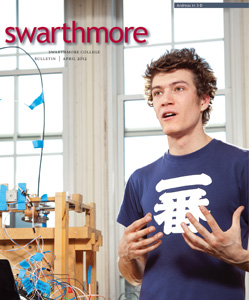

It has been close to four years since Werther bought the company, after almost three decades contributing to the success of others. In his office adjoining the product room, Sorbee’s owner and chief executive officer neither looks nor acts like a stereotypical business tycoon, despite his crisp shirt, floral tie, and gray pants with well-polished black shoes. He speaks clearly but softly and exudes youthful enthusiasm as he explains how the company—his company—moved two years ago from smaller quarters to allow for future expansion.

By the time Werther bought Sorbee, at age 47, he had more than two decades of experience as a lawyer and businessman under his belt.

After graduating from Temple University School of Law, he was a business lawyer for firms in his hometown, Philadelphia, and in New York City. Then, he became interested in becoming a businessman himself, bemoaning the isolation that is the lot of most lawyers.

“Law is so much different from the business world,” Werther says. “With law, you’re working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The business world allows more time—with five-day weeks—and that was really different for me. And I had more of a penchant for business and certainly more of an interest.”

During the 1980s, he began to move away from business law to managing businesses. By 2008, he was at a crossroads.

“I’d been a lawyer, business operator, fundraiser, and banker, but I still had to figure out what I really loved,” he says. “It turned out to be operating a business, but I had yet to do it for myself. That’s why I bought Sorbee. I bit the bullet and wrote the check. I own 100 percent of it, and I run it on a day-to-day basis.

“Sorbee was a likely target, considering its food and confection orientation as well as its large and consumer-facing business model—these were actually all things I’d enjoyed and worked with in the past,” Werther explains.

“What motivated me was the fact that Sorbee had great products but an absentee management. I believed that with time and attention, I could establish my own imprint on the business, fix some things, and use it as a platform to acquire other branded food/snack/confection/possibly organic food-related businesses or business lines in the future.”

As a business owner, Werther carefully decides which products to sell under the Sorbee name. Since buying the company, he has secured an ongoing licensing deal with Kraft under that manufacturer’s Crystal Light and Country Time trademarks for use in candy products—Crystal Light sugar-free hard candies and Country Time full-sugar lemonade hard candies, currently Sorbee’s two largest-selling product lines.

“The hard-candy market is small, compared to everything else,” he says. “There is a much-larger market for chocolate and gummies.” To compete with sales of other companies, Sorbee created Crystal Light sugar-free fruit chews, and Country Time fruit chews are to come soon.

For a new business owner in pursuit of a deal, talks at the negotiating table may be tense—with an occasional touch of melodrama.

Early in 2010, in preparation for the introduction of a new line of syrups, Werther worked with a licensing agent to first approach diet brands such as Weight Watchers and Nutrisystem that would sell his sugar-free syrup under their companies’ names. He explains that sales of sugar-free syrup had been mediocre at best and to prevent the line from being discontinued, it needed to be bumped up with a good license. He planned to seek brand names not only to endorse the sugar-free syrups traditionally manufactured by Sorbee for diabetic consumers but with an eye to including full-sugar varieties as well. He came close to signing a contract but reconsidered. Instead, he suggested his agent reach out to restaurant chains.

The agent’s pitch enticed the International House of Pancakes (IHOP)—the largest breakfast chain in the country, which had just initiated a licensing program—to offer Werther a contract for Sorbee to become IHOP’s sugar-free syrup licensee.

Werther, his chief financial officer, head of sales, and head of marketing and product development flew to Los Angeles to the IHOP headquarters. Anticipating the value of the contract they were about to sign, they were excited. “We thought that with the IHOP name, we could turn our sugar-free syrup from a $500,000 line to $5 million line. We couldn’t have been happier.”

Once in the board room, Werther and his three colleagues sat on one side of the table. Moments later, close to a dozen IHOP executives walked into the room. “I’m thinking, ‘There’s something disproportionate about this. Something doesn’t look right,’” Werther recalls. “We hadn’t been asked to prepare a presentation,” he says. “So I winged it, and when we were done, IHOP’s position was, ‘You guys are good. We have a lot of friends at Walmart [which carries Sorbee’s Kraft-branded products]. You have a good reputation there. But we just don’t think that launching your first IHOP-branded product as a sugar-free syrup is the right way to go.”

Werther and the Sorbee executives didn’t know how to react. “I think I even started packing up my stuff,” says Werther.

But the meeting wasn’t over. He continues: “Then, one of the senior executives reached over, put her hand on my arm and said, ‘But you guys have a really good reputation. We think you should consider taking our entire retail syrup license.’”

Sorbee owner Dan Werther is not only a businessman but also a philanthropist. At the 2010 Sweets and Snacks Expo, he set up a Crystal Light Candy poster board, pledging to honor all who signed it by donating a certain sum for each signature to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

About one month later Werther signed a long-term exclusive deal with IHOP, which, together with sister restaurant group Applebee’s, forms the business for a public company known as DineEquity Inc. The deal guarantees Sorbee the IHOP license for the next decade. At the end of last year, Sorbee launched all of

IHOP-branded syrups via mass merchandisers around the country.

In the months since signing the license contract, Sorbee employees have worked on new syrup products, designing a unique bottle and crafting flavors, labels, and packaging. “We think we have everything perfect,” Werther says.

He’s enjoying life as a small-business owner. Having missed personal contact with clients as a lawyer, he says, “I love the small company atmosphere, because you get to know everyone, both on a professional and personal level. Each individual brings his or her unique qualities to the job. I’m a coach and mentor, but everyone does multiple jobs. Some CEOs only oversee, but all of us are really engaged in what we do, and, as CEO, I need to learn, too.” There’s been very little turnover among his staff of eight.

The staff size may change soon, though. Werther anticipates that the company, whose revenue has been less than $10 million until now, will grow, with revenue from the syrup alone expected to exceed $15 million.

“By next year,” he says, “the business is expected to almost triple in size.” He gestures in the direction toward the large central space. “That’s why I’ve kept that space in the middle empty. ”

Email This Page

Email This Page