WEB EXCLUSIVE: Touching Generations

Ink on paper still resonates across the decades

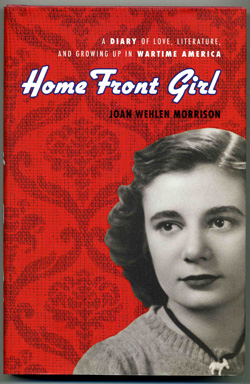

Susan Signe Morrison ’81 edits her mother's diary entries written from the perspective of a college student during World War II.

At a dinner organized at the Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility to welcome Sherri Kimmel, thenew Bulletin editor, to Swarthmore, members of the Board of Managers were asked to share something about the College she might not know. I mentioned the phone booth near Parrish Commons where every Sunday at 3 p.m. I would call my parents in New Jersey. Oh, the days before cell phones!

That sparked a memory from Jane Lang ’67. People would have hall-phone duty—you’d sit in a chair next to the phone with your homework and wait for calls to come in. If a girl got a call, you’d go to her room and knock and see if she was there. If not, you would leave a message that someone had called. A common one was MNM (Male No Message). These were the days before emails and Facebook! Jenny Hourihan Bailin ’80 mentioned letters her parents had saved that she had written to them about her life here as a freshman. Jorge Munoz ’84 said he wishes his dad had saved his, but he only has the letters his dad had sent to him.

I found those memories about saved letters particularly profound. After my mother’s death in 2010, I found several of her journals from the 1930s and 1940s. I transcribed and edited her diaries into a manuscript that the Chicago Review Press published as a young-adult history book in November titled Home Front Girl: A Diary of Love, Literature, and Growing Up in Wartime America. This diary provides a record of what an everyday American girl felt and thought during the Depression and the lead-up to World War II, 1937–43, from ages 14 to 20. My mother, Joan Wehlen Morrison, was an oral historian who went on to become an adjunct professor of history at the New School for Social Research. This book is her own oral history, unearthed decades after she composed it.

Certainly the diary is an important primary source—a vivid account of a real American girl’s lived experiences. As a scholarship student at the University of Chicago “junior college” (junior and senior years in high school) and then as an undergraduate at the U of C from 1940 to 1944, Joan was an intelligent, humorous, insightful, self-mocking, and pensive reader of her times and the people around her. She describes her daily life growing up in Chicago and ruminates about the impending war, daily headlines, and major touchstones of the era—FDR’s radio addresses, the Lindbergh baby kidnapping, the novella Goodbye Mr. Chips, the film Citizen Kane, Churchill and Hitler, war work and Red Cross meetings.

Yet how she experienced college is incredibly familiar, even to students now attending Swarthmore. She records how she and her friend Betty often discussed boys. “I was moaning to Betty about how they all go off their nuts when they meet me—… Larry, well, he certainly acted strange on the roof. I wouldn’t not call that kiss—that conversation—conventional. Betty says I’m the type they like to cuddle. God, I’m the intellectual type—as you undoubtedly know. Well, I don’t know whether it’s better or not they go nuts when they meet me—but at least it makes life interesting. …” One boy evens tries to romance her by reciting the Greek alphabet to her. His attempt, needless to say, fails.

While Joan excelled in most humanities classes, her German teacher at a Christmas party “sees me and nods, smiling. … He makes an announcement and it is only afterwards I learn he has said the punch is spilled. My German is none too good. But the almond paste cookies are. I eat a great many.”

Not all the information in her notebooks is utilitarian. In psychology class on Jan. 19, 1943, after notes about Pavlov’s dogs and conditioned responses, Joan wrote, “Dog gets neurotic if compelled to make too fine a distinction. Me too.” Then she drew a picture of a dog salivating. Amongst her scribbles about John Donne’s poetry, igneous rocks, and Aztec gods are doodles of girls’ heads and dresses, the actress Dorothy Lamour, and an “anthropologist gone native” in his sarong. There are numerous messages to her friend Betty. These entries vary from the frivolous (“Look at the long haired lad in the row ahead” and “Oh, this is deadly,” evidently concerning a boring lecture in history class) to the conversational (“Are you going to Northwestern next quarter?”) to the epic (“Germany Declared War This Morning!!!”).

Much of what she writes concerns the war and how it has affected and will affect her generation, one that grew up in the wake of World War I. She writes, “Now it is nineteen-forty. The long awaited and prophesied death year. It is almost over. It is midnight in the autumn of 1940 as I write. The poplar leaves crunch under the foot when one walks and the chilly winds are here already. Far away a streetcar grinds and a child cries. London is being bombed. “

Much of what she writes concerns the war and how it has affected and will affect her generation, one that grew up in the wake of World War I. She writes, “Now it is nineteen-forty. The long awaited and prophesied death year. It is almost over. It is midnight in the autumn of 1940 as I write. The poplar leaves crunch under the foot when one walks and the chilly winds are here already. Far away a streetcar grinds and a child cries. London is being bombed. “

On Christmas 1940 she walks in downtown Chicago, “Then on Michigan Blvd. I passed suddenly the Cunard window. … An exhibit for the British War Relief—pictures of little children in Britain—homes bombed—helmets that could be knitted for the RAF—a noble purpose—but it’s making war in our hearts. … The little German children are bombed and hungry too. … And all the sudden, in an emotional intensity, I thought, ‘This may be the last Christmas we shall have’ … I should be wise and know the world will never end.” The summer of 1941 she works at a factory inspecting army rations and tries to alleviate the tedium by reciting A. E. Housman and Shakespeare’s sonnets to herself.

You come to identify yourself with your college. Joan was assigned Hitler’s Mein Kampf in one class so they could understand the motivations for the war better. “Woman stopped me on street today as I was carrying Mein Kampf for sociology and asked me if that’s what they taught me at the U of C. I defended my school—though it hurt.” The importance of our college years is, as we all know, seminal for who we become. “It’s wonderful going to my school. I’m proud of it, of its ideas, of its cool democracy, of its dear honesty. It’s good to go to a school you believe in.” At the end of her freshman year in 1941, she remembers “how I cried once in Freshman Week. … We were singing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ with my eyes shining wet, looking down at the circle of people we were to know, far below on the dance floor. Somehow that first faraway day, I seemed to see the end before the beginning began … I seemed to see us all old while we were still young. I seemed to see us all parting before we had met.”

And then, on Dec. 10, 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the war really hit close to home. “The Japanese paratroops have captured Luzon in the Philippines and sunk two British ships, the Repulse and another near Singapore. Hitler speaks to Reichstag tomorrow. We just heard the first casualty lists over the radio. … Lots of boys from Michigan and Illinois. Oh my God! … Life goes on though. We read our books in the library and eat lunch, bridge, etc. Phy Sci and Calculus. Darn Descartes. Reading Walt Whitman now.” Robert Maynard Hutchins, the president of the University of Chicago at the time, was an idol for Joan, as her journal makes clear. When she heard his speech “The Proposition Is Peace: The Path to War Is a False Path to Freedom” on the radio in March 1941, she enthusiastically embraced its sentiments. Yet when she and 2,000 of her classmates heard the university president’s speech after war was declared, he “says we should win the war now that we’re in it.”

As an anthropology major at the University of Chicago, Joan was told, quite seriously, by one of her male professors that the only way a woman could become an anthropologist was to marry one. Joan would have seen these journals with the eye of an anthropologist. She believed that everyone has a story, even though he or she may not yet realize what it is. As she presciently wrote on Oct. 19, 1941, “To understand one’s story is to weep with pity.”

I understand why Jenny and Jorge are so moved to have handwritten letters from their time as students at Swarthmore. I have come to believe in the value of writing on paper, not on an electronic medium like a blog. True, with a handwritten letter or journal you cannot include links to cool websites or pop-ups or have a soundtrack. But nothing can replace the physical presence of the ink trails carefully traced by a human hand. The writings you or your parents or your friends compose may be touched one day by readers of another generation. The very act of making contact with what you personally touched will be so meaningful to them. Insights to your time will make the past blaze into life for them, and with that kindled light, your essence will glow as well.

Susan Signe Morrison’ 81 is the Swarthmore College Alumni Council President 2011-13

This article contains excerpts from Joan Wehlen Morrison’s Home Front Girl: A Diary of Love, Literature, and Growing Up in Wartime America, edited by Susan Signe Morrison ’81. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2012.

You can also read an essay by Morrison on her mother's diaries at “This I Believe.”

Email This Page

Email This Page