Overcoming Dioxin’s Devastating Effects

Phi and Phu (foreground) are brothers who have managed to transcend their disabilities. They’re pictured with their mother, Hoang Thi Tuyet, and other family members.

Sometimes the simplest changes make a huge difference for Vietnamese people with physical challenges caused by dioxin exposure.

Trinh Thi Tam paid a high price for moving supplies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War. Her face is pockmarked with chloracne from dioxin exposure, and her son Luc has been an invalid his entire life. A poor woman, Tam has only a small vegetable plot. The Red Cross wanted to give her a couple of pigs to raise and sell.

American Susan Hammond, who used to live in Vietnam and founded the nonprofit War Legacies Project, remembers Tam’s response: “You’re crazy. I have to walk a mile every day to get water. I do it at night because I have to leave my son alone, and I worry about him. … If I have pigs, I’m going to have to walk even more to get water for them. I can’t do it. What I need is a well.”

With funding from the War Legacies Project, Vietnam’s Red Cross had a well dug 65 feet deep and bought a pump. A neighbor offered to let Tam tap into his electricity if she shared the water. Tam and several neighbors now do so.

This woman who had been a charity case to her neighbors now has something vital to share, Hammond points out. The dynamics shifted, and they “became more of a community.” Charles Bailey ’67 observes that Trinh now has neighbors concerned about her well-being, “a form of social security.”

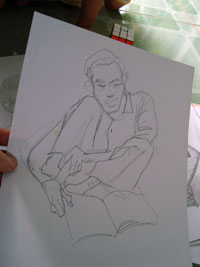

Phu is a talented artist who has learned to create art with one hand, propelled by his foot.

Then there is the case of Nguyen Van Hoai Tan. Now 22, he was unable to walk or sit up in bed until World Vision, a Christian humanitarian organization, provided training in physical therapy for his mother, Nguyen Thi Le. She worked with him for years until, at about age 16, he could sit up on his own. His mother then taught him to manipulate his hands, so he could hold chopsticks, and he began to “drum on pots and pans and entertain himself,” Hammond says. “He loves music.”

Tan’s ability to sit up, says Hammond, changed their lives. “He went from a child who was just lying there, could do and see nothing but the walls, to being able to sit up and look out the window while his mother was working in the garden.” Now he can even join her in the garden by sitting in a wheelchair donated by another charity.

Given the chance, individuals with disabilities can shine, as evidenced by two brothers, now in their late 20s, who grew up having to live on the floor. Phu is bent like a pretzel, his legs tucked behind his ears. For years, his mother, Hoang Thi Tuyet, bicycled to primary school with him and his brother Phi, then carried them inside the school on her back. When they entered secondary school she bought a motorbike and drove them. She and another brother built Phu a low desk so he could sit on the floor.

The brothers were excellent students, and after finishing high school, they tutored many students after school. Donations from a French-Vietnamese businesswoman enabled the family to build a new house with a classroom for tutoring, and the War Legacies Project purchased electric wheelchairs for Phu and Phi. Now they can literally look their students in the eye. Phu is also a talented artist. He paints by managing to propel his good hand with one foot.

Email This Page

Email This Page