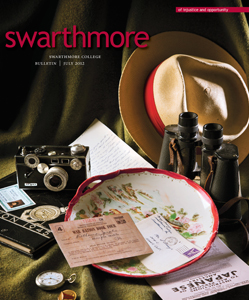

Unpacking Memory

Teacher-artist Randall Exon lets his imagination be his guide

Artist Randall Exon in his studio. Click below for a video featuring Exon. Photo by Laurence Kesterson

It’s hard to believe Randall Exon, professor of studio art, is approaching his 30th year of teaching at Swarthmore. His looks—especially his lush locks—his energy, and his forward momentum as a teacher and painter suggest it just couldn’t be so.

A proud product of the Great Midwest, Exon exhibits an unguarded nature that is typical of natives of that region. He also has a can-do attitude, another Midwestern trait, which he brings to the classroom, the studio, and his work with College committees.

When he spoke with Bulletin editor Sherri Kimmel in May, Exon was being featured in a show at the Walton Art Center in Fayetteville, Ark. He has work in a Woodmere Art Museum exhibition that explores the “warping” of realism until July 15. Next February, he’ll mount his fourth one-person show at Hirschl & Adler Modern in New York, the gallery that represents him.

While he’s been a mentor to many budding artists, he has had mentors of his own who’ve helped make his 30 years memorable and productive, in particular the late Gilmore Stott, associate provost emeritus and associate dean of the college, and his wife, the late Mary Royloff Stott ’40.

When we look at a landscape that you have painted, are we looking at real places or are they imagined places?

The most recent work that I’ve done tends to be more from my imagination. I go to Ireland every year. I come from Kansas and Nebraska, and I’ve lived out here in Pennsylvania now for the past 30 years. So I’ve got these three places that are all in my head at the same time. The reason I love Ireland so much is it reminds me a lot of the Midwest that I grew up in. It’s very much an agrarian culture. In the back of my mind, there’s always this sort of connection to my past and the Midwest. When I make a painting, there are different parts of those experiences that come into the work. Part of it has to do with light in particular. It’s not necessarily a kind of light that I would associate with this region or Ireland or the Midwest. But it’s kind of a combination of all those places.

It’s not a duplication of reality.

If people want to call it romantic, I suppose it is, but I don’t think of myself as a romantic, necessarily. One of my big influences growing up wasn’t a painter, but Southern writers. Flannery O’Connor made a huge imprint on me. The dark spirituality in her stories resonated with me for some reason. I went to the University of Iowa as a graduate student, and in those days, I could go into the library, and I could take to a table on my own, not even wearing gloves, her M.F.A. thesis and just look at it, with her notes on the margins. There was something about Southern fiction that really stimulated my imagination. That’s why I’m still a representational painter, because subject matter and poetics bring different recognizable elements together. There’s a fictional aspect to my work. I’m not trying to create a real place. I’m trying to create something from my imagination, but it’s based on something that I’ve experienced. But that experience tends to veer more toward memory, and memory becomes something very cloudy after a while.

Would you say there’s a spiritual dimension to your work?

I think there is. It’s my outlet, in a way. There’s something about certain types of composition, arrangement of shapes and shape relationships, and then connected with a kind of light, that speaks to something deeper about the human condition and experience and nature and our place in nature. But memory is what I’m primarily preoccupied with, and trying to unpack memory a little bit. I might see a subject that seems to remind me of something. And as I paint it, that memory seems to get closer to me. So the best paintings bring me to a place of recognition. It’s not necessarily a comfortable place. Beauty, for me, always has a little bit of sadness associated with it. I’m the type of person who’s going to paint the flower when it’s just starting to lose a little bit of its bloom. I find that a little bit more interesting. The minute I saw Caravaggio, he just knocked me for a loop, because his apple in a still life has little wormholes in it, and the leaves have little holes in them from bugs, and there’s this entropy there that is fundamental. It’s important to recognize it in life. I find it quite beautiful, actually.

You mentioned Caravaggio. Are there other artists whom you see as models?

Growing up, there were a couple of people, like Georgia O’Keeffe. I remember a big article on her in Life magazine when I was 8 or 10 years old—and seeing this white bleached skull of a steer against this flag and then these paintings of the desert. Andrew Wyeth too. As a young person, his work resonated with me quite a bit, for the same reasons that O’Keeffe’s did and [Winslow] Homer’s and Edward Hopper’s. Hopper I think more of as a really fine designer of pictures that elicit through their design such a powerful and immediate meaning. Nighthawks is a painting that has always stuck with me. And I’m not actually that crazy about the way it’s painted.

Is that the one set in the diner?

The diner, yes. It’s not very luscious paint. It’s not like French paint, you know?

Right. It’s kind of muted.

It’s matter of fact. It’s relatively flat in some ways, and his models have a kind of mannequin quality. I didn’t look at it and see all those faults, because they’re not faults. They actually work in that painting in a peculiar way to generate this kind of emotion or mood.

I want to ask you about a particular painting of yours, which hangs above the mantel in the president’s house. It has a special resonance for President Chopp. She even used it as a backdrop for her recent TEDxSwarthmore talk. Can you talk a little about that painting?

It almost seemed providential. When I heard that Rebecca was hired for the job, I was immediately taken with the fact that she grew up in Kansas, and not far from where I grew up. We have this kind of funny history in common. I went back to Nebraska and South Dakota and Kansas and did a series of paintings. Fred [Thibodeau, Chopp’s husband] heard about this, and he commissioned a piece for her inauguration. It’s a painting of the Flint Hills in Kansas, which bordered on the areas where I grew up and where Rebecca grew up. It’s a beautiful, open area, range country, for the most part. But it’s really the only stretch of the original prairie that exists out there. So it has a kind of a prehistoric quality. It’s quite beautiful. Big skies. That’s what I was trying to get at in that work, and they [Chopp and Thibodeau] seemed to really appreciate it, which for a painter means everything. People have asked me over the years, how can you sell your paintings?

I remember when I was young thinking the worst thing I could imagine was having a basement full of my paintings when I’m old that my family would have to figure out how to get rid of. I’ve been fortunate that over the years they became part of people’s lives and part of their families, and that means more to me than anything. I love for them to get out and live their own lives.

Besides being a working artist, you’re also a teacher of art. How do you balance your life as a teacher and a practicing artist?

It is a balance, but it’s symbiotic. I need one for the other. I’ve been doing it so long that retirement is not a very comfortable word for me. There are points during the academic year where I think, “Geez, this is too much. I’ve got to get back in the studio.” It’s a little bit like a practicing musician. If you stop for a couple weeks, it takes a while to get going again. As I become more of a senior person around here, I tend to get a little bit more committee work than I used to. But I love it. I love the school. I care about the place a lot. You start thinking, “Oh, what are these changes going to mean here and there?” That’s another Midwestern thing. If somebody asks you to do something, you’re going to do it. And if they appreciate it, then you’re really stuck.

Email This Page

Email This Page