It’s Getting Better All the Time

“I wanted to be in an urban school where the kids needed my attention,” says teacher Sara Posey ’04. But it wasn’t an easy start for her or the ambitious new Chester Upland School of the Arts.

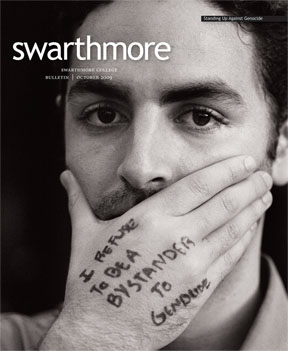

Sara Posey ’04 is a first-grade teacher at the new arts-based Chester Upland School of the Arts located in Chester, Pa.

It couldn’t get much worse.

A few weeks into her new job teaching first grade at the Chester Upland School of the Arts (CUSA) in fall 2008, Sara Posey could barely force herself to drive to work. “I felt ill, physically ill. I thought the whole school project that I was so hopeful about and so passionate about was turning into a disaster,” she told me months later. It didn’t turn out to be a disaster, but neither was it easy for Posey, who cares deeply about her teaching.

Posey wasn’t some green first-year teacher. After student teaching while at Swarthmore (where she was a music and education major and vocal performer), Posey taught first and second grade for four years at The School in Rose Valley, a private elementary school near Media, Pa. But she had jumped at the chance to work at CUSA during its inaugural year. The school is the brainchild of John Alston (watch: Alston discusses CUSA) , associate professor of music at the College and founder of the Chester Children’s Chorus (CCC). The school—housed in an old but serviceable four-story school building in the heart of Chester, Pa.—was starting its first year with students in pre-kindergarten through grade two.

“I knew I would miss my kids at Rose Valley,” Posey said, “but they ultimately would do fine without me. I wanted to be in an urban school where the kids needed my attention. Rose Valley’s a child-centered school with a project-based curriculum, integrated across subject areas—just the sort of approach that the School of the Arts was promising. People have said that won’t work for inner city kids, but I can’t believe that’s true.”

The challenges proved to be greater than she imagined—both in and beyond her sunny second-floor classroom. Although a handful of her 20 students could read simple words and sentences, more than half entered first grade not yet knowing their letters. By late September, the predictable chaos of the first day of school—the day that Posey learned that her students had no experience sitting in a circle on a classroom rug—had hardly abated.

“My kids were out of control—they couldn’t listen to each other,” she remembers of those weeks in late September when she struggled to make herself go to work. “My classroom assistant had quit, and there was no replacement. I didn’t understand what was happening, and I couldn’t go to my boss [the principal] for help, because it turned out she didn’t know what was happening either. So I felt ill, and I had to tell myself: ‘Okay, you made it to work. You drove all the way here. Good job. Now you just have to make it until [the kids go to] fine arts. Good. It’s 10:30. Congratulations! Now you have to get from lunch to recess. Can you do it? Good. Another day. Now you get to drive home, and you made it, see? You didn’t give up.’”

THE CHESTER UPLAND SCHOOL OF THE ARTS—which opened for its second year last month with grades pre-K through three—exists because, like Sara Posey, a whole lot of people didn’t give up. An unusual public-private partnership that is neither independent nor charter school, CUSA began in the imagination of Alston, who founded the Chester Children’s Chorus 15 years ago. Alston saw that the chorus was able to reach a small number of Chester’s children for just a few hours a week. Its Summer Learning Program provided those same children with an intensive five-week artistic and academic experience—but there was a deeper need across Chester for innovative approaches to education.

The Chester Upland School for the Arts was started by Associate Professor of Music John Alston (above).

Chester is the poorest city in Pennsylvania. Nearly 30 percent of its 36,000 residents live below the federal poverty line, currently $22,050 for a family of four. After years of declining enrollment and fiscal problems, its public school system, the Chester Upland School District, was taken over in 1994 by the state, which placed several Chester schools under contract with the for-profit Edison Schools in an effort to improve test scores. According to Education.com: “After a number of years, it was determined that Edison was not successful in turning the district around. A number of incidents, including an allegation of sexual misconduct on the part of an Edison employee, and policies such as not allowing students to bring books home, led to the state’s decision to break its contract with Edison.”

Despite the fact that it annually spends about the same amount per pupil as the highly rated Wallingford-Swarthmore School District—it continues to score at the very bottom of the state’s rankings. In 2008, just 11 percent of Chester Upland’s high-school juniors were at or above grade-level proficiency in reading and just 3 percent reached proficiency in math.

In 2004, Alston recruited a small group of educators, community leaders, and other professionals to help him open a new kind of school in Chester—with the shoot-for-the-stars goal of “preparing Chester students to enter the finest colleges and universities in America.” The proposed school would be arts-intensive, modeled after such successful projects as the 45-year-old Harlem School of the Arts. The group investigated forming a tuition-free independent school or a charter school and found that the former would require daunting sums of money and the latter was fraught with political problems within the school district, where more than half of elementary school students now attend charter schools, draining children and dollars from the traditional public schools. Eventually, the group, with Maurice Eldridge ’61 as chair and Alston as president, formed The Chester Fund for Education and the Arts, a nonprofit corporation that sought a new kind of relationship with the Chester Upland district.

The solution—reached only after new district superintendent Gregory Thornton was hired in 2007—was an unusual public-private partnership. CUSA is a public school housed in a district-owned building just two blocks from Chester High School. Children are admitted to the school by lottery on the basis of parental interest. The school’s staff members are district employees, and CUSA receives the same per-pupil funding as any other public school in the district.

But The Chester Fund, through a memorandum of understanding that Thornton enthusiastically endorsed, provides additional funding that makes possible smaller class sizes (20 instead of 30 children); an assistant teacher in each classroom; up-to-date instructional technology such as computers and smart boards; and an enhanced arts program that includes music, dance, and visual arts instruction. An extended day program, mandatory for second grade and above, offers small-group tutoring, academic enrichment activities, and specialized arts instruction leading to performance opportunities.

After five years of work and planning—and several frustrating trips down blind alleys—CUSA opened in fall 2008 with 200 students in two sections each of five grades (pre-K3, pre-K4, K, one, and two). Opening day was bright and sunny, and Alston was there, beaming and leading all the students in song. Superintendent Thornton and new principal Corinne Ryan were also on hand. It was a dream come true—almost.

I SPENT A TUESDAY AFTERNOON IN EARILY November in Posey’s classroom. After the children left for the day, Posey said: “There are things that are going better all the time—a lot is going better. But there are still some things that aren’t great.” There had been the inevitable tensions with the school district that attend the start-up of a new kind of public-private model, and Principal Ryan had departed. An interim principal had been named—not a bad change, to Posey’s mind.

(Wendy Emrich, managing director of The Chester Fund, said later: “Everyone involved with the principal selection did the best job they could, but as the weeks and months went by, it just didn’t seem to be a good match for the school or for the candidate.” In spring, a search was undertaken for a new head of school for fall 2009, resulting in the appointment of new principal Janet Baldwin.)

Although a new classroom assistant had been hired in late October, Posey had gone weeks without one, and she was visibly tired. We sat on little first-grade chairs, our knees nearly touching our chins, as she showed me a student’s writing folder, citing “concrete improvement.” She was teaching the children to write down the sounds they hear when they pronounce a word: “Say ‘remember’ and write down the sounds that you hear.” Sometimes what they wrote actually looked like “remember,” and Posey saw progress in that.

As a Swarthmore student and after college, Posey had spent many hours with John Alston’s Chester Children’s Chorus, helping out at rehearsals during the school year and working as a counselor at the chorus’s Summer Learning Program. As he is for many at the College and in Chester, Alston has been an inspiration to Posey.

In 2002–2003, Posey teamed up with Professor of Educational Studies Ann Renninger and others to design and run a research project to investigate children’s feelings of self-efficacy and learning in the CCC. They learned through a series of interviews and sight-reading assessments that chorus members were not only gaining musical knowledge but also social skills and habits of learning. The kids—especially the older ones who had been in the chorus for several years—were learning how to think like musicians. As they learned more about music, they experienced an initial waning in their beliefs about their musical competence, and then later a resurgence of this music self-efficacy, all the while exhibiting greater confidence and independence in and out of the choir. Posey and Renninger conclude that “arts-based programs can be organized to provide a complex of developmental opportunities for children…” and that the “goals and expectations of the program [clearly state] that achievement will be hard and also that [chorus members] can and are expected to achieve. This programming provides participants with the kind of counter narrative that promotes identities of achievement and underlies the social mission of the CCC.”

There’s growing evidence that cognitive functions and learning can be improved by arts study. In a Dana Foundation study released in 2008, researchers from seven universities examined the question: “Are smart people drawn to the arts, or does arts training make people smarter?” Among the researchers’ findings were:

• An interest in a performing art leads to a high state of motivation that produces the sustained attention necessary to improve performance and the training of attention that leads to improvement in other domains of cognition.

• Specific links exist between high levels of music training and the ability to manipulate information in both working and long-term memory; these links extend beyond the domain of music training.

• Correlations exist between music training and both reading acquisition and sequence learning. One of the central predictors of early literacy, phonological awareness, is correlated with both music training and the development of a specific brain pathway.

• Learning to dance by effective observation is closely related to learning by physical practice, both in the level of achievement and also the neural substrates that support the organization of complex actions. Effective observational learning may transfer to other cognitive skills.

According to a cautiously optimistic summary written by Michael Gazzaniga, director of the Sage Center for the Study of Mind at the University of California–Santa Barbara, who oversaw the Dana Consortium research, “The preliminary conclusions we have reached may soon lead to trustworthy assumptions about the impact of arts study on the brain.”

A significant portion of the report focuses on emerging neuroscientific evidence of correlations between arts study and cognition. Although Gazzaniga emphasizes the differences between correlation and causation—and, further, between “weak” and “strong” evidence of each—the report concludes that with certain kinds of arts training, especially in music and dance, “cognitive improvements can be made to specific mental capacities such as geometric reasoning; that specific pathways in the brain can be identified and potentially changed during training; that sometimes it is not structural brain changes but rather changes in cognitive strategy that help solve a problem; and that early targeted music training may lead to better cognition through an as yet unknown neural mechanism.”

BUT AS INSPIRED AND PREPARED AS POSEY WAS, she said she had a lot to learn about the first-graders in her CUSA classroom. The distance between Swarthmore and Chester—or between The School at Rose Valley and CUSA—is very few miles but almost impossible to fathom in other dimensions, and it weighs on her. “I don’t know,” she said. “I worked with the choir, and I hear John’s voice saying, ‘It’s just down the road. It’s just 10 minutes.’ But there’s no comparison between the preparation for school that first-graders have here [in Chester] and the preparation they have in Swarthmore. But there are developmental things that are the same for every child. I’m very sensitive about framing this community in terms of deficit. It comes off as snobbish and classist and maybe even racist. People make a lot of assumptions about children based on race and class.”

According to Kids Count, the student population of Chester Upland schools is 80 percent black—but it’s poverty in Chester that seems to have a more significant effect on school readiness. A study last year by neuroscientists at the University of California–Berkeley confirmed for the first time that the brains of low-income kids function differently from the brains of high-income kids. Nine- and 10-year-old children differing only in socioeconomic status (SES) were found to have detectable differences in the response of their prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that is critical for problem solving and creativity. It had already been established that children from resource-poor environments have more trouble with the kinds of behavioral control that the prefrontal cortex is involved in regulating, but the new study found clear functional differences among low SES kids.

“It’s a wake-up call,” said Robert Knight, director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute and the School of Public Health at Berkeley. “It’s not just that these kids are poor and more likely to have health problems, but they might actually not be getting full brain development from the stressful and relatively impoverished environment associated with low socioeconomic status: fewer books, less reading, fewer games, fewer visits to museums.”

Pediatrician and psychobiologist Thomas Boyce, who co-authored the study with cognitive psychologist Mark Kishiyama, noted that previous studies have shown that, by age 4, children from poor families hear 30 million fewer words than do kids from middle-class families. “In work that we and others have done,” Boyce explained, “it really looks like something as simple and easily done as talking to your kids” can boost prefrontal cortex performance.

Pediatrician and psychobiologist Thomas Boyce, who co-authored the study with cognitive psychologist Mark Kishiyama, noted that previous studies have shown that, by age 4, children from poor families hear 30 million fewer words than do kids from middle-class families. “In work that we and others have done,” Boyce explained, “it really looks like something as simple and easily done as talking to your kids” can boost prefrontal cortex performance.

THIRTY MILLION WORDS? REMEMBER HOW MANY questions 3- and 4-year-olds ask? And if those questions are responded to seriously, children learn to listen too. “Listening is a big thing,” Posey explained, thinking about the school day that had just ended when I next visited CUSA, in February. “At Rose Valley, I could read almost anything and hold the children’s attention. Here, I have to choose more carefully what I read aloud. And then there’s the pouting.”

I had noticed this problem too. When a few of the children didn’t get their way—sometimes on matters that seemed wholly inconsequential—there often ensued major pouting and withdrawal from the group. Sometimes the child was angry, sometimes there were tears, but more often it was a demonstration of body language and facial contortions that said, “I’ve been hurt by this disappointment, and I’m not going to participate any more.” To the point, Posey told me, that this behavior was really holding them back.

“So I developed a little lesson on pouting,” she said. “I set goals for each of the children. Many of my goals are behavioral—lining up, listening, quieting down. We’re trying to teach how to learn, not to retreat, but to stay engaged. That’s one way I measure success.”

Other measures are more concrete and bureaucratic. As in all schools these days, there is lots of testing at CUSA. Posey is philosophical about standardized measurements of the students’—and the school’s—progress. (And, indirectly, her efficacy as a teacher.) The curriculum for each subject in each grade is mandated by the district, and teachers are expected to use the materials provided—what Posey calls “boxed curricula”—such as “Everyday Math” or “Storytown.” Teachers may create their own lessons or projects, but they must think—and document—how each project is intended to achieve district and state standards. They must also reach certain curricular milestones at set times during the school year, before testing occurs.

Other measures are more concrete and bureaucratic. As in all schools these days, there is lots of testing at CUSA. Posey is philosophical about standardized measurements of the students’—and the school’s—progress. (And, indirectly, her efficacy as a teacher.) The curriculum for each subject in each grade is mandated by the district, and teachers are expected to use the materials provided—what Posey calls “boxed curricula”—such as “Everyday Math” or “Storytown.” Teachers may create their own lessons or projects, but they must think—and document—how each project is intended to achieve district and state standards. They must also reach certain curricular milestones at set times during the school year, before testing occurs.

Lisa Smulyan ’76, professor of educational studies and associate provost of the College, who volunteered in Posey’s classroom last spring, said that the advantage of packaged curricula is that “they put it all in one package for you, and they sequence it in a way that seems to reflect what we know about kids’ learning.” But, she said, it’s difficult for the excellent, handpicked teachers such as those at CUSA to create a rich, arts-integrated environment and still meet the curriculum demands of the district.

“There’s no time in the teachers’ day in this country to do that kind of work,” Smulyan said. “The kind of shared thinking and planning that would allow teachers to take more control over the canned curricula takes time. I think it’s a huge problem everywhere—it prevents teachers from collaborating.”

The school day had been busy and complicated. I followed Posey and her class into the CUSA computer room, which was bursting with new Macintosh machines. The computer time was in lieu of outdoor recess on a bitterly cold day, and the first-graders loved it—a Mac for each of them, more evidence of The Chester Fund’s enhancements of the CUSA experience. Later, accompanied by Posey’s new teaching assistant, Michelle Freeman, I walked with about half of Posey’s class to the dance studio, where full-length mirrors, a “sprung” floor, and a great sound system give the school’s full-time dance instructor, Melisa Putz, the space and tools she needs to teach groups of up to 20 children. There’s also a well-equipped art room and a large music room—an overall set of arts facilities that many public elementary schools in the country, and none in Chester, can boast.

Still, as Smulyan points out (and Posey confirms), there’s little time for the arts teachers to interact with the classroom teachers to plan together. CUSA offers a rich program, but can it live up to The Chester Fund’s idealistic description of a school “where all children will sing, dance, and do visual arts every week as integral parts of the academic curriculum and as separate subjects?”

Still, as Smulyan points out (and Posey confirms), there’s little time for the arts teachers to interact with the classroom teachers to plan together. CUSA offers a rich program, but can it live up to The Chester Fund’s idealistic description of a school “where all children will sing, dance, and do visual arts every week as integral parts of the academic curriculum and as separate subjects?”

AGAIN, POSEY DIDN'T GIVE UP. NO LONGER ILL, NO LONGER FORCING herself to drive to work, she’s beginning to see what CUSA is and what it can become. In late March, she tells me there’s a science unit coming up in Pearson Science, the boxed curriculum, about sound. The lesson teaches the children that sound is actually a vibration in the air. So is music, Posey reasons, and off she goes.

On April 16, she and music teacher Helen Hagerty collaborated to team-teach the penultimate lesson in a science unit. It’s not in the district-supplied box; in fact, it’s way outside the box. I was invited, but when I got there, Posey said, frowning, there’s “sort of a problem.” Hagerty’s regular second-floor music room had been commandeered by district officials for a VIP event. So the lesson, which was planned for right after lunch, had been postponed to last period of the day. “Cranky time,” said Posey, making another face. (Like most good first-grade teachers, her face communicates almost as powerfully as her voice.)

Posey spent a week preparing the children for the musical experience. They learned about how their ears work and how sound is one of their senses. They learned the three important ways that vibrations create sound and music in their ears—the shaped air of voices and wind instruments, the induced vibration of strings, and the deliberate crash of percussion. Making a quizzical face this time, Posey asked the children, “What’s the difference between noise and music?” It’s a pretty big question for first graders, but after a few hands were raised, they arrived at the idea that music is organized noise. Then it was time for direct experience with musical instruments that make sound in these ways.

Her music room off limits, Hagerty had improvised in CUSA’s “gym,” a large carpeted room in the basement. She created stations around the room, each representing a different kind of sound production, each with a half-dozen instruments for the children to experiment with. Most were sturdy enough for first-grade hands, but a few seemed risky, like Hagerty’s own acoustic guitar and her homemade dulcimer. But she said, “I trust you to take good care of these.” And the children did.

Her music room off limits, Hagerty had improvised in CUSA’s “gym,” a large carpeted room in the basement. She created stations around the room, each representing a different kind of sound production, each with a half-dozen instruments for the children to experiment with. Most were sturdy enough for first-grade hands, but a few seemed risky, like Hagerty’s own acoustic guitar and her homemade dulcimer. But she said, “I trust you to take good care of these.” And the children did.

Each child—and here was the essence of the science/art lesson—was armed with a clip board and worksheet that asked them to record what they found at each station. What kind of instrument was it? How was its sound produced? What vibrates? How can you change the sound? As the children rushed from instrument to instrument, the teachers and I—a former elementary-school art teacher caught up in the excitement—kept bringing them back to the questions. Since Newton, this has been the scientific method: What do I sense? How did it happen? What does it mean?

To wrap the science unit up, the children made their own musical instruments. Cigar boxes, rubber bands, lentils and beans, cans, paper towel tubes, and other recycled materials were fashioned into homemade wind, string, and percussion instruments. At the CUSA spring concert, the first-grade scientists got to play their own instruments in the “orchestra.”

A FEW WEEKS LATER, with the end of CUSA’s first year in sight, Posey came to the College (“it’s just down the road, just 10 minutes”) to speak with Thom Whitman’s [’82] class Music, Learning, and Arts Integration. Comparing her experience at Rose Valley, where many of the students had observed, to CUSA, she said, “At Rose Valley, you have hardly any constraints. You know what you’re responsible for teaching, but you can create anything that is interesting to you and to your students that addresses these standards.” She showed video of A Powerful Potion, an opera written by first- and second-grade Rose Valley students in collaboration with the music and art teachers. “Teachers need to justify and explain when they do such things,” Posey says. “But this project, centered on the study of opera, had components of language arts, music, art, social skills—even math.”

When she talked about CUSA, her frustrations were clear. Her kids weren’t prepared for first grade. The boxed curricula are limiting. And, at the heart of the matter, there’s not enough time to collaborate, to integrate the arts into her teaching. She had hoped for a better-defined commitment to being an arts-based school. But there are good things too. The families of her students have been “wonderful, extremely helpful and supportive.” And every one of the kids who didn’t know his or her letters in September is now reading.

We meet again two weeks later. Posey has the worn-out look that teachers get in the spring, as they count down to the end of school, now just six weeks away. “The warm weather makes a big difference in how psychically ready I am for it to be over. That false spring in March was hard. It felt like all of a sudden it was spring, but I hadn’t taught them enough. There were still people who couldn’t read well enough, who couldn’t listen well enough. I felt really negative. But now that it’s truly warm, I can say, ‘Okay, we’ll make it.” She seems happy and confident, seasoned by the year behind her.

We meet again two weeks later. Posey has the worn-out look that teachers get in the spring, as they count down to the end of school, now just six weeks away. “The warm weather makes a big difference in how psychically ready I am for it to be over. That false spring in March was hard. It felt like all of a sudden it was spring, but I hadn’t taught them enough. There were still people who couldn’t read well enough, who couldn’t listen well enough. I felt really negative. But now that it’s truly warm, I can say, ‘Okay, we’ll make it.” She seems happy and confident, seasoned by the year behind her.

But it won’t be easy. Posey has learned that Michelle Freeman, her “terrific, awesome” classroom assistant who has been her partner since October, has just gone on maternity leave earlier than expected. There’s testing coming up, and the kids will be “testing and testy” because Freeman is not there. “They get so grumpy when their worlds are disrupted. Really, really emotional,” Posey says. “It sounds more judgmental than I mean it, but many of these kids don’t get what they need emotionally. When babies and preschoolers and primary kids get the emotional support they need, they begin to act in a more emotionally mature way.”

“Do you feel a sense of accomplishment about this year?” I ask. Here’s where Posey described the problems with the first principal—about barely being able to drive to work and making it through the day one period at a time. But then she says “yes.”

“When did things start to get better for you?”

The turning point was a teacher-training session with a “really good speaker who said to focus on one thing, not to feel like you have to be excellent at everything. I wasn’t a first-year teacher, but obviously in many ways I was, because I hadn’t worked in an inner city public school. Just having her say that the ‘good teachers of kids in poverty don’t say, Well it should be this way and it should be that way. The good teachers of kids in poverty say, This is what we have. Let’s do something.’ That was freeing. It made me feel less emotional and ill to feel like, okay, this is what it is and we’re going to move forward.”

The teaching staff at CUSA have been “awesome, committed, passionate, devoted to the children. I have so much respect for them. Without that team, I personally wouldn't have made it, and the school certainly wouldn't have made it,” Posey says.

She also feels very supported by The Chester Fund. “Without that, we wouldn’t have arts. We wouldn’t have assistants. Our classes would be 30 instead of 20. We wouldn’t have had smart boards. I went to CUSA because I wanted to do arts and to be in a place that would support me in treating children like people. I felt pretty secure, knowing John Alston as well as I do, that the children would be respected and that we would be striving for the best in education.”

Sara Posey began her second year of teaching at CUSA on Sept. 8. “The school year has started beautifully,” she reports. “Most of my kids went to kindergarten here, and I keep thanking the kindergarten teachers for preparing them so well. Many of them are reading already.”

By adding a new grade level each year, CUSA expects to be a pre-K3 through grade eight school by 2014. To date, The Chester Fund, an independent nonprofit unrelated to Swarthmore College, has raised more than $3 million in support of the school. And the Chester Upland School district hired two new student-support staff members for CUSA this fall.

Email This Page

Email This Page