Jettisoning the Baggage

Studying religion—especially Islam—brings “responsible scholastic practice” face to face with personal faith.

Al-Jamil largely does not believe that the sensitivity of religious subject matter in general—and Islam in particular—should affect its teaching in any special way.

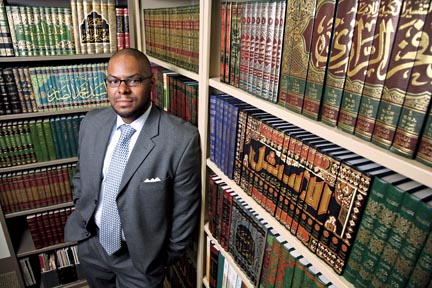

Tariq al-Jamil, assistant professor of religion and coordinator of the recently approved Islamic Studies Program, is endowed with a certain mystique. Al-Jamil casts a different aura—maybe due to his colorful ties, classic suits, and black designer glasses (a talking point for fashion-minded students) or his striking physiognomy. But it also has to do with his teaching style.

All who have taken a class with al-Jamil can attest to both the breadth of his erudition and his sometimes bewildering habit of cutting himself off mid-lecture and switching topics. A hint of ironic self-awareness as he does this banishes any suspicion of absentmindedness and arouses curiosity. Was he about to enter a realm too theologically complex for students to follow—or, more possibly, approach a point of religious or social sensitivity from which he then withdrew?

After all, Islam is currently endowed with an especially charged geopolitical status. In post 9/11 America and Europe, terrorist stereotypes and hostility toward Muslims abound, while in parts of the Islamic world, perceived slights to the dignity of Muslims spark protests and violence. The academic study of Islam seems more necessary than ever but also fraught with potential pitfalls.

Al-Jamil largely does not believe that the sensitivity of religious subject matter in general—and Islam in particular—should affect its teaching in any special way. Concerning the difficulties that might seem inherent in teaching a class made up of both believers and nonbelievers, he says: “I personally feel it is not the role of the professor to avoid investigating questions that would impinge on truth-claims. We are studying religion through a multidisciplinary range of lenses: historical, anthropological, sociological, and literary.” Faith, moral values, mystical experience, theological systems—the components of religious existence—may be discussed but never be subjected to direct evaluation, so that neither believers nor nonbelievers need back away from such scholarly investigation.

Al-Jamil strives to give equal consideration to different or opposing traditions of knowledge that make up his discipline. He never allows his personal views about various Islamic theological sects to trickle into his teaching, applying a criterion of responsible scholastic practice that he says is generally valid for more than just the treacherous terrain of religion.

The reasoning behind such an argument is rooted in the fundamentals of epistemology. Every discipline needs a basic set of givens, or “a priori laws,” to determine what counts as legitimate knowledge or argumentation within that field. No academic discipline can function by directly attacking the base on which it is built, (although theoretical ground can shift over time). Moreover, such an a priori foundation is not monolithic or self-justified: It is composed of overlapping and conflicting premises held by competing intellectual traditions within the field as well as general assumptions made by outsiders. These inevitably must be balanced.

“All disciplines are careful not to impinge on the presuppositions of their students or colleagues,” Al-Jamil says.

Even in physics, careers may be built on separate theoretical frameworks (eg. traditional particle physics versus string theory) that appear irreconcilable, he says. Such competing views cannot and do not simply dismiss each other. His analysis has logical force.

Yet, there remains the profound sense that religion is somehow different from other domains. Professor Steven Hopkins, chair of the Religion Department and a scholar of South Asian religions, talks about what makes the study of religion particularly complex.

“The challenge is, you’re not studying something that is neutral to people’s experience. You’re studying traditions that make truth claims, that are about ultimate ideas and existential aspects of people’s lives,” he says.

Hopkins does not favor, in the name of objectivity, aggressively pursuing topics that would undermine “the self-understanding” of religious beliefs: “I come from a particular school of thought that says religious people should be able to recognize themselves in your scholarship. That makes studying religion different from, say, the study of Proust. There are interfaces with living persons of faith, who are part of your study, that makes it complex, that makes it negotiated and transactional.”

Hopkins recognizes that all professors of religion do not share this view: “There are scholars who have immense insights but who have little or no interest in religious perspectives and kind of a disdain for religion itself. They study the texts historically. So you don’t necessarily have to be sensitive to religiousness to be a scholar of religion.”

He believes a range of approaches is essential to the discipline and contributes to the overall strength of a program like Swarthmore’s. “Religion is a subject matter that needs many perspectives. Our department has always been dialectical, dynamic, elastic.”

At the other end of the spectrum are professors for whom the classroom can be a place for spiritual awakening or exploration.

“I’m not there,” Hopkins admits.

Al-Jamil is more blunt. “My [own] faith should have nothing to do with [my teaching],” he says. “I’m a professional through and through. I find it to be a problem when a teacher privileges his own presuppositions in the classroom and quashes those of students. The teacher [of Islam] who says ‘this is the way we did things when I was growing up in Pakistan, so I know how it is’—that is intellectually shoddy.”

On the other hand, neither does al-Jamil believe that the sensitivities of religious students deserve special consideration. “The academic study of religion is designed to bring traditional understanding into dialogue with a broader intellectual discourse. All academic learning is about jettisoning the baggage of preconceived notions, and religion is no exception.”

Al-Jamil’s no-nonsense view of intellectual rigor finds support among Muslim students.

“Tariq doesn’t censor himself,” says Humzah Soofi ’10, who took his first Islamic Studies course last year. “He doesn’t step away from hot-button issues. The American Muslim community tends to be very apologetic, like when talking about the concept of Jihad. They insist that Islam is really peaceful. But Tariq is willing to tell us that Islam, like any religion, is not exempt from violent discourse and, also, as in other religions, neither does Islam necessarily prescribe nonviolence.”

Ailya Vajid, a senior religion major with an Islamic Studies minor, agrees. “Tariq gives you all the good and bad about your religion, so you know you can trust his class. You can begin to come to terms with things like the complex and challenging Koranic passages on slavery.”

The academic study of Islam has enriched the personal religious lives of both these students and bolstered their understanding of inherited traditions, they say. Vajid admits taking some of what she has learned in class—such as postmodern commentary on the Koran—“with a grain of salt,” but she has found much that is indispensable. “I come from a minority within Islam—Shi’i—and before I got here I knew nothing of the history or development of our particular sect.” She says that Al-Jamil, who specializes in studying Shi’ism—especially its medieval incarnation—has helped her in that regard.

Soofi, who grew up in a traditional Muslim community and could read the Koran in Arabic by age 12, says: “Where I grew up, there was not much chance to question why we do the things we did. We just did them. I think looking critically at the reasons for these practices—like praying five times a day—can deepen and round out my belief.”

Eli Epstein-Deutsch is pursuing a self-designed major in modernist studies and is co-founder of the student magazine The Night Café. He took Tariq al-Jamil’s course in fall 2006.

Email This Page

Email This Page

March 4th, 2010 12:31 am

Sadly teacher pre-suppose their beliefs on their students far too often these days. Sadly I guess it is a sign of the times.

August 3rd, 2010 10:24 pm

I agree, Jeff. It is indeed a sign of the times. I do believe that many mainstream Educational institutions are not sensitive to the religious faith of their students.

August 21st, 2010 6:03 pm

Agree with Jeff and Zoe. I see bias' played out every day at my school and the faculty that should be supportive of all religions are anything but sensitive. In some cases they are absolutely less than indifferent.